I first knew Sharon Patten sitting next to my cousin Kathe, both their heads upside down, scratching their dandruff into the folds of a magazine with Elvis booming in the background, “I’m all shook up.” Uh-huh-huh, uh-huh-huh, scratch again.

Who could shed the most dead skin? Their daily uniform consisted of a man’s long-sleeved button-down white shirt and bermuda shorts. If one turned the corner of State Fair Blvd. into Third Street, one might see four legs hanging from one tree in Sharon’s front yard, their two hidden heads plotting new clubs such as Do Whatever I Tell You Club which one day comprised walking backwards down our main street downtown, Ohio Street. We did. Hardly anyone noticed.

A visitor sinking down into Sharon’s living room sofa might have been surprised to see four eyes staring up through that glass-topped coffee table: Sharon and Kathe concocting yet another club like the Qwertyuiop whose mission became the shoebox homes for their animal creations drawn from wooden stamps or bookmarks: their Beatrice Potter world?

With Sharon’s attractive mother, Lucy, shifting her attention to her various husbands, Sharon then moved in with her grandfather, Marion Hall, who encouraged her interest in horses. I thought she must be in heaven as her grandfather owned the local dairy and its irresistible and all she could-ever-want-to eat Tullis-Hall ice cream.

Sharon and I began to ride horses together when she was eighteen. Even though she was nine years older than me, she treated me like an equal. Besides our love of horses, she invited me to her house and into some of her world.

My first vision of Sharon’s world was her opening drawers either side of her bed, revealing the shoebox creations from the Qwertyuiop Club, those miniature houses with tiny creatures at home inside, every detail fitting, easeful. I was entranced. I began to notice even as she carved carefully with her even white teeth a select bite of a snickerdoodle (her mother Lucy’s specialty), Sharon’s eyes. They seemed considering, not just the luxurious, dissolving sugar and cinnamon on our tongues but some inner rumbling, perhaps even tastier.

My grandmother, Sharon, my mother Mary, her grandmother, and Sharon’s mother Lucy at my 10th birthday party at the Sedalia Country Club in 1962.

Sharon had the knack of nurturing nature into art. To celebrate one Halloween, she transformed her gorgeous horse, Prince, into an African Chief using saved chicken bones and Prince’s own hay for his tribal dress. Like the horses in the cave at Chauvet from 30,000 years ago, Sharon’s art also grew out of her natural world. When Prince was accidentally electrocuted, Sharon’s life collapsed, broke down. Yet, it was this terrible time and turmoil that brought her art from her core. She stood up, chose art and got her B.F.A.; then won a Guggenheim Fellowship.

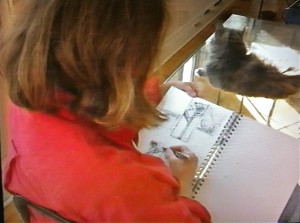

In her studio in Kansas City, her multitude of cats crisscrossed her canvases in the morning light, keeping her close to the thing itself–her expression, combing her breath, cat stroke and brush stroke. It took a lot of paint for Sharon to get to her point. Windsor and Newton loved her (and did the toxicity in paint kill her, one can’t help but wonder?). Layer upon layer of oil spread with a palette knife was Sharon’s technique. She was not driven but drawn to paint. She said in an interview that it was her own honesty she discovered. That was the most important thing, to follow that central impulse to who you are. Her thick paint and patterns, often on oversized canvases seem to charge the world to fess up.

She took the palette knife straight from her heart to us. From miniature cardboard to her later magnificent oil canvases stretching over nine feet, the breath of Sharon’s vision is still warm. Shoeboxes and shadows, horse sense and cat sinewing, Sharon’s magnanimous strokes strike still, attesting to her courage and wisdom. She tunes us back to wonder.

0 Comments