The first fact about Eugenie to come to mind is 98, 98 times marvelous. There is no thud of years about her. Entering her Russian salon, each person is received by Eugenie with genuine interest. She reigns amidst her art and historical artifacts, beneath her Russian icons, a wise spirit not so much respiring as inspiring, agreeing with Keats:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

Eugenie and her twin grandchildren, Ilhana and Owen.

A Love of Art and Education: ‘Art Chased Me’

“I always wanted to go to college. My brothers were encouraged to go to college but not me because I was a girl.” Eugenie felt betrayed. When all of the parents of the Trenton, New Jersey high school seniors were inside watching the graduation at the War Memorial in the park near the edge of the Delaware River, Eugenie and her four girlfriends sat on the wall outside. “There were seven hundred graduates, and we never went inside. I think my parents thought they saw me!” The four friends saw the ceremony as hollow since they, as girls, were not allowed to go on to college. This was 1940.

While in high school in the late 1930s, Eugenie took art lessons in New Hope, Pennsylvania, a thirty-minute drive from Trenton. Saturdays they would pile into the teacher’s station wagon and drive to a field in Pennsylvania to paint. Her father knew well the Delaware River painters, a local group of artists. He was a Russian colonel and aristocrat who worked as an artist when the family moved to New Jersey in 1925. “The arts were a part of Russian training, and my parents always encouraged us to be artists if we could.”

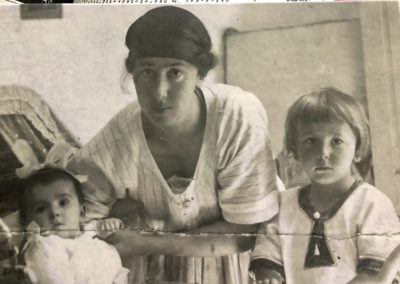

Eugenie’s mother, Baroness Alexandra von der Launitz, with her three children: Eugenie, Alex & Ted.

Eugenie’s mother, a Russian baroness, was classically trained in painting. It was at one of her mother’s dinner parties that Eugenie fortuitously met Alma, a PR person for Lenox China. (Founded in Trenton in 1889 by Walter Scott Lenox, Lenox China was the 20th century’s most prestigious American maker of tableware, creating the first North American bone china to be used in the White House.) Alma asked Eugenie all about her art training and eventually got her a job working at Lenox as an intern with Pat Eaken.

“Pat Eaken was my boss and exposed me to the world of art. She took me to Washington DC, to the Mellon, the National Gallery of Art. There I saw my first Georgia O’Keefe paintings. They were so strong the paintings. O’Keefe was married to Stieglitz who opened her as an artist. I was a poor working girl but interested in what they were doing. Pat really educated me into the world of art.” Pat was a designer at Lenox, hired in an effort to bring the china industry to the U.S. She designed a line of fine china figurines made with American clay that today are considered rare collector’s items. Eugenie worked with Pat on those figurines. (You can read a little bit about Lenox and Pat Eakin in a 2008 Trenton Potteries Society newsletter here.)

A Family of Artists

Eugenie’s mother was Baroness Alexandra von der Launitz, who served Czarina Alexandra and can trace her lineage to Rurik, who in the 9th century became the first Russian grand prince. Her mother was also a Red Cross nurse during the first world war. Her father was Col. Theodore N. Ediss of the Czar’s White Army. With the 1917 revolution, her father as part of the White Army (the anti-Bolsheviks) had to flee the country. Chased by the Bolsheviks, he drove his wife in a horse-drawn cart south from St. Petersburg to the Crimea on the Black Sea. As they fled, her mother wondered what was making that whistling sound all around them. It was the bullets from the Bolsheviks. As her husband whipped the horses faster, she felt like a rabbit in headlights, horrified as they passed young Orthodox priests hanging from trees like animals.

The Ediss family: from left: Eugenie’s older brother Alex; her father Colonel Theodore Ediss; Eugenie; her mother Baroness Alexandra von der Launitz; and Eugenie’s younger brother Ted.

The Kurds came down from the mountains to give refuge to the White Russians. They had supplied horses to the Czar’s army. Her mother told Eugenie it was like arriving into “the Arabian Nights” with the King and Queen of the dynastic Kurds and their child greeting them. They were so beautiful, colorful, flamboyant. From there her parents were able to cross the Black Sea in a French Red Cross ship for Turkey, eventually making their way to Yugoslavia as the King of Yugoslavia was a friend of the Czar’s. There Eugenie was born January 7, 1923. Eventually, the family immigrated to Trenton, New Jersey in 1925.

Her father first got a job in an iron foundry. When Mr. Schuman, the owner, heard there was a Russian aristocrat working in his factory, he met him, saying he too had been an immigrant. He had arrived from Poland with only a nickel in his pocket. Mr. Schuman got her father a job with the Mueller company, a ceramics company that made decorative architecture, designing ceramics for wealthy New Yorkers for their pools, doorways, for churches. He drew a cartoon first and then transferred it to sheets of clay. He would carve it and glaze it. Mrs. Schuman arrived one day in a chauffeured car at Eugenie’s house. She brought a beautiful doll with a lavender organdy dress and a china face and hands, made in Europe. Eugenie found it too refined for her. Her only doll was a working man’s doll with eyes that didn’t open and close and that wore her kind of clothes.

The Depression of the ‘30s brought an end to her father’s job at Mueller’s. He applied for a job at a bigger ceramic factory that made hotel china for the White House. He would sit up until two in the morning drawing the commemorative plates. Later he came to LA and found a job as a set designer for Columbia Pictures. In his garage in Lakewood, CA, her father opened an art studio. His lady pupils would always ask him to finish their paintings, saying “‘Show me what to do with this.’ He even finished my mother’s paintings! He was so intense with his help that he forgot the pupil he was meant to be helping.”

In 1964 Eugenie was accepted into the new art department at UCI. She was 41 years old, married and with a son. She didn’t think she would qualify because she had gotten Cs in sciences in school. But she did. Tony Delap, the painter, and John Mason, the sculptor, were her first art instructors at UCI. They encouraged Eugenie. After two years, they said they would sponsor her in the master’s program. They gave her a four-year scholarship. She had to take all the prerequisites like English 101. Eugenie got her BA.

In 1969 when Eugenie graduated at UCI, her father was very proud and came to her graduation. “I never liked Picasso but it’s ok that you studied him,” he conceded. “Father was a conservative art lover. Not interested in abstract art. He did say that he wished he had studied it though, so he could understand Picasso’s techniques.”

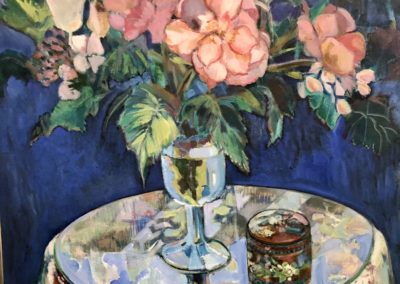

Still Life by Eugenie Fisher.

After Eugenie’s father died, her mother, Alexandra, went to Cerritos College when she was 83 to study art. She was on their college catalog cover. As a girl in Russia she had her own studio attached to her bedroom on the Baltic Sea. “My mother was a romantic. She would fall in love with anyone if they had talent. She was a wonderful pianist.” Eugenie’s mother also loved gardening.

“Mother also was very social. When she read in the newspaper about some Russian relative the families had in common, she would immediately call them. That’s how Mother found Missy, the daughter of Princess Maria Poutiatine. Missy went to Orthodox church every Sunday, wearing a blue hat, blue gloves, blue shoes. Missy and Eugenie became friends. Missy had seen Eugenie’s brother’s photo on the mantlepiece and wanted to meet him. So one day Eugenie took her brother Alex with her to meet Missy at her sorority house. Missy came running down the stairs with a large scarf around her just washed hair. They all jumped into the car for a ride and it wasn’t long before they were married. Alex and Missy had seven children, six boys and one girl.

Missy’s mother was from Russian royalty, like Eugenie’s. Missy’s father was a terrific flirt. “Imagine him flirting with nineteen-year-old me!” He had a mistress and Missy’s mother used to call her “the grasshopper” as she hopped from bed to bed. Missy’s mother spoke Oxfordian English: “Don’t be surprised if you find lettuce in your drawers and lace in your refrigerator,” she told Alex, the groom to be. Missy was not a housekeeper. She would lock herself into a room with a book. Alex had to employ a nanny to look after the seven children. When Missy’s mother lost her husband, she went to Lebanon to a Greek Orthodox convent and became a nun. The fasting was so severe in Lent, the convent’s stone floors so cold and hard on the knees, that Princess Maria got pneumonia and died there. Missy went to fetch her mother’s body, but it took her weeks to get her home as there was some kind of revolution which closed the airports in Beirut.

The Mariinsky Theater in Saint Petersburg.

As a graduation present to herself for obtaining her degree at UCI, Eugenie bought herself a ticket to Russia. Although she went alone, she met up with a group from Capistrano. They had tickets to a matinee performance of the Russian ballet in St. Petersburg. The Russians dressed very formally for this, putting the more casual Americans to shame Eugenie thought. That was until the Russian man sitting in front of her took off his dress jacket as he couldn’t stand the heat anymore. (It was well into the 80s F.) He only had a t-shirt on underneath. Eugenie will never forget the freckles on his sunburnt neck and back.

Russians are great readers and art lovers according to Eugenie. They treasure culture more than anything material. “Just think of the Russian ballet or the Hermitage, probably the greatest art collection in the world. When I was a kid, I went to the library every Friday and when I would find an author like Tolstoy or Turgenev I liked, I would try to read everything they wrote. Think of Tolstoy’s skill in creating the consciousness of so many characters in the same room at the same time. His wife had to have a cottage built for him behind their house so he could perform all his different characters out loud without disturbing the neighbors.”

Eugenie and her son Jay on her 90th birthday.

Dorrie Dunlap also inspired Eugenie. She was head of the art department at OCC. Dorrie specialized in pastel painting. Eugenie loved it. “A flood of joy would go through me. This is a wonderful thing to be doing, like an epiphany. I was doing something I really loved.” Dorrie had great faith in her and invited her to join her in London at the Royal College of Art where David Hockney, a favorite of Eugenie’s, had studied. “Because Dorrie was faculty she could go. She rented an apartment on Queen’s Highway and within walking distance from college. I had a fellowship and we had a lot of fun, not just with art but shopping at Harrods.” Dorrie had arranged an exhibition for Eugenie’s art at the local library but she died suddenly.

“I dream a lot about art. I dream I’m painting.” Lately, Eugenie has been dreaming of building houses from watery blue and green sheets of elegant cardboard, like an endless puzzle. Art keeps Eugenie company. People also do. Eugenie is interested in everyone. Presently, she is teaching one of her caregivers Russian. They sing songs together and laugh a lot.

Further Reading

• Czar Treatment, a 1997 LA Times article about Eugenie

• The Newark Museum Presents a Glimpse of Its Lenox Collection

• A January 2000 Trenton Potteries newsletter that mentions the work of Pat Eakin and the history of pottery manufacture in Trenton, New Jersey

• Potteries fo Trenton Society website

• History.com’s Russian Revolution

• UCI’s Claire Trevor School of the Arts

Photo Gallery

-

Eugenie's 90th birthday celebration.

-

Eugenie’s mother with infant Eugenie and brother Alex.

-

The Ediss Family.

-

Still Life by Eugenie Fisher.

-

Samovar by Eugenie Fisher

-

A painting of her grandparents by Eugenie.

-

Eugenie and her beloved dog Reggie.

-

Eugenie’s maternal grandfather Baron Peter von Offenberg.

-

Eugenie and her twin grandchildren, Ilhana and Owen.

-

Young Eugenie in her garden.

-

Eugenie's maternal grandparents.

-

Eugenie with her twin grandchildren.

-

Eugenie’s father, Colonel Theodore Ediss.

0 Comments