As I left the front door this morning, I saw the moonflower folding on its vine. A whiff of regret swept over me for the subtle and seductive scent dissolving, the green sepals forcing that purest white leaf inward. I stopped myself and looked hard at the dying flower, that single moonflower lasting but one night: its dying form had its own beauty.

I saw I had been missing something by not stopping, not looking hard. I sensed there is a morality in every moment, a moral obligation to be present, not just to the sensuously pleasing but also to the sensuously unpleasant (and what often upon closer look has a peculiar beauty despite the tired tread of age).

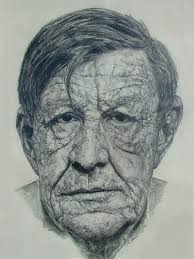

As W.H. Auden (pictured below), an old master himself, wrote, “About suffering they were never wrong, The Old Masters: how well they understood…how everything turns away quite leisurely from the disaster.” No one particularly likes to look at the ravages of age head on with the exception of doctors or scientists who study them.

The poet Wordsworth wrote about aging in a poem about a different flower from the moonflower, about a small celandine that stopped him as he walked through the woods.

“…But lately, one rough day, this Flower I passed

And recognized it, though in altered form,

Now standing as an offering to the blast,

And buffeted at will by rain and storm.

I stopped, and said with inly-muttered voice,

It doth not love the shower nor seek the cold;

This neither is its courage nor its choice,

But its necessity in being old.”

The moonflower and the celandine both fold and fray not with courage or choice but by necessity of age, like those of us who live long lives. Yet that aged stance, that “offering to the blast” whether straight, hammertoed or with walker or wheelchair, that stance takes courage.

If we don’t look hard, we will miss it, we will miss them. The word dotage signifies not just dottiness or feeblemindedness but to dote, to give attention. Our older ones deserve to be doted upon.

-

The moon & its flowers

-

Moonflower in the night

-

Dying Moonflower

-

Moth in Moonflower

-

Auden's map of age

-

The lesser Celandine

0 Comments