“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

— Margaret Mead

Jean Watt

December 16, 1926 – April 16, 2023

Our friend Jean Watt, the legendary Newport Beach community activist, passed away at her home on Sunday, April 16. Jean was 96 and lived a life well-lived. She channeled her good heart, her strengths, and her organizational and leadership skills into serving others: most notably as a local environmental and community activist for 50+ years, and as a Newport Beach City Council Member from 1988-96. Jean was practical, down-to-earth, and unwavering in her efforts. She continued to work, advising and supporting others until the end of her life.

Below is a piece we published in our Coral Tree newsletter earlier this year, a compilation of two interviews my mom and I did with Jean.

I know I speak for all of us at Coral Tree who spent time with Jean when I say that her presence, friendship, and wisdom has been a gift in our lives.

Thank you, Jean for your lived example; and for encouraging us to see that ordinary people with common sense, patience, and the will to serve — qualities we all possess and can develop — can accomplish extraordinary things. From our hearts, thank you.

INTRODUCTION

Our friend Jean Watt is an example of how a heart of service and action, level-headed and stable compassion, common sense, and the courage to lead and work with others can accomplish great things.

Since the 1970s Jean has been working to preserve Newport’s natural world and heritage — and make our city and county a nice place to live.

Her founding, in 1974, of Stop Polluting Our Newport (SPON), a non-profit that for half a century has served and protected our local environment and citizens, is perhaps her most precious gift. (In fact, SPON’s 50 years of grassroots initiatives — many aimed at keeping unskilled commercial development in check — have been so successful that they updated their name to Still Protecting Our Newport.)

Jean has also formed and led a handful of other organizations over the years that help care for, protect, and preserve our natural spaces and neighborhoods (at the bottom of this piece you can find links to the organizations Jean founded); and supported countless community initiatives, individuals, non-profits, causes, and projects.

“I’m very lucky to have my four kids. Because getting older, it’s sort of a burden. And if you can share it, you’re better off.”

In 1988, when she was 61, after 15 years leading SPON and heading various successful environmental and other local livability initiatives that forced the city and local developers to listen to the voices of Newport’s citizens, Jean ran and was elected to serve on Newport Beach’s City Council.

“We need to … conserve Newport Beach as a good place to live,” Jean told the LA Times in a 1988 article, “Jean Watt Steps Down From the Bleachers,” published after her election that year. “But it’s a major misinterpretation to call me a no-growth person…

“… Growth is beneficial, as long as it allows an area to function at its highest and best use. In Newport Beach, I think that is more an enjoyment of the natural marine environment than as a financial Mecca. Ten years ago, slow growth was a bad term and so — to a lesser degree — was environmentalist. Now, practically everybody is an environmentalist and slow growth is seen as OK. I think that’s progress.”

The people agreed, and Jean ran and was reelected for a second term. She served a total of eight years, stepping down in 1996 — just shy of turning 70 — but has never stepped away from serving others. To this day, at 96, she continues to serve on SPON and other local and non-profit boards, offering her support, experience, and wisdom to all who seek her out — a kind advisor and friend for the greater good.

Through our interviews with Jean, and also in reading various articles like the 1988 LA Times piece, and from watching interviews about Jean’s life and work (there are three great videos on the Newport Beach Historical Society website where Jean talks about her summers in Newport in the 1930s) — the main refrain you hear is: What can I do to help? How can I be of benefit to others: to my family, my community, my country?

This mantra: How can I serve? seems to have been the inspiration for so much of Jean’s life — certainly for her decisions to become a nurse, a Girl Scout troop leader, a volunteer-activist, and a non-profit, political and community leader.

And this deeply ingrained wish to be of service — which Jean says she saw in her parents, and also in the Beeks, particularly Carroll Beek — is perhaps one of the primary factors in her success. She’s in it for others, not for herself.

And from that seemingly simple aspiration — and acting upon it — extraordinary results have come.

Jean also persevered in what she felt was right, and had the foresight to see that endless and unskilled development doesn’t make for a nice place to live; that trees and green spaces, and clean waterways aren’t just nice for the local plants and animals, but also fundamental for the human beings that live here.

She’s also balanced — as you can hear in her quotes to the LA Times — another one of her strengths. In fact, when Jean and friends started SPON: “We weren’t primarily an environmental group,” she says in the same piece. “But most of the problems we were facing were environmental. We had seen citizen groups disband after an immediate goal was achieved, and we had also seen developers picture one organization as radical that had been fighting for a simple height ordinance. I didn’t like the idea that a group with legitimate objectives could be put down that way and then divided and conquered. I thought we should be able to rise above that.”

“If we don’t collectively decide what we want and be able to articulate that politically and in a in a broad enough way, then we are simply at the mercy of the developers whose objective every day is to look and see what they can buy — and there’s nothing wrong with that — but they’re not going to have the community’s best interest at heart.”

She’s also never given up or been swayed by the inevitable challenges that come with doing good work or pursuing a worthy goal.

As her friend Nancy Gardner wrote in “You Must Remember This: Superjean,” published in Stu News Newport in February:

“How does she do it? How does one person accomplish so much? One of Jean’s strengths is her quiet approach to things – quiet, but steady. She has a remarkable ability to keep her eye on the prize. Opponents have not always been pleasant. She shrugs it off. The goal is what’s important and she helps everyone remember that.”

And not only humans and future generations have benefited. Jean’s service to others has also included our ecological community: the local flora, fauna, and all creatures — great and small — our neighbors, with whom we share this world.

A wise, compassionate, stable heart has no limits.

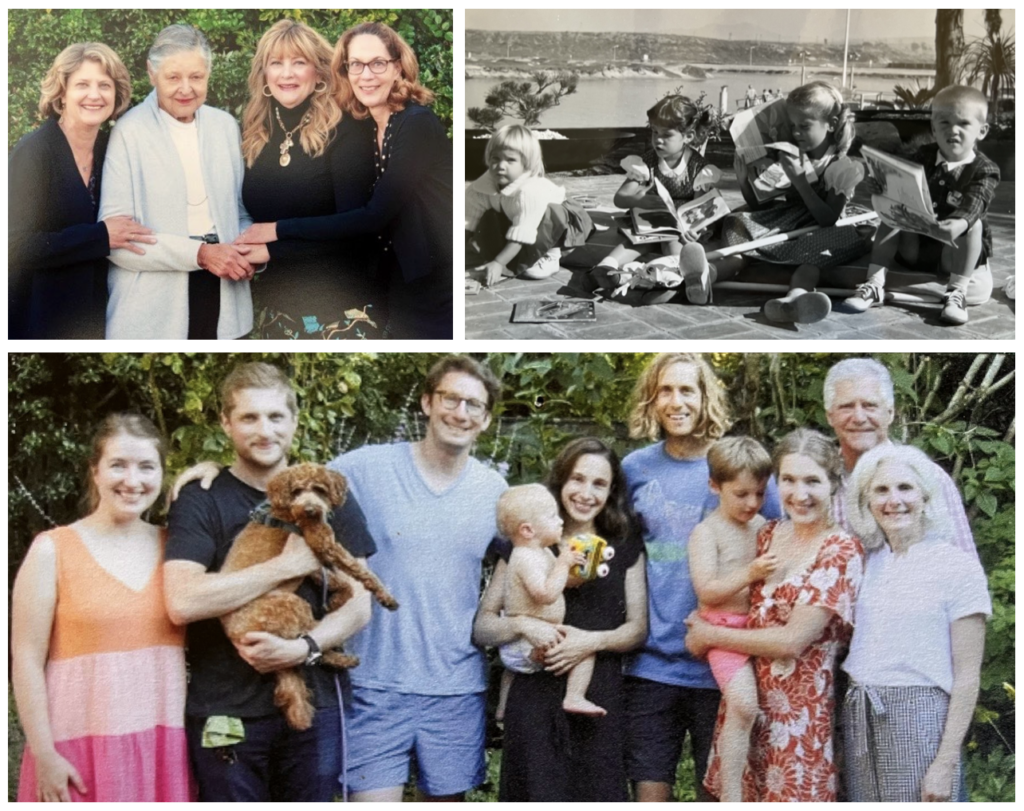

She is also clearly is a wonderful and loving mother. In any interactions with her children — and from reading about the praise they had for their mom when she was honored with the Newport Beach Citizen of the Year Award in 2013 (Nancy mentions this in her Stu News piece) — you can hear their shared love and respect.

B E G I N N I N G S

Jean’s Childhood & Pre-Community Activist Story

The daugher of Lorna and Herbert Hahn, Jean was born on December 16, 1926 in Pasadena.

Growing up, Jean was hugely influenced by her connection to and experience in the natural world.

At home in Pasadena, Jean was free to roam and play, climbing trees and building forts on her family’s 20-acre property.

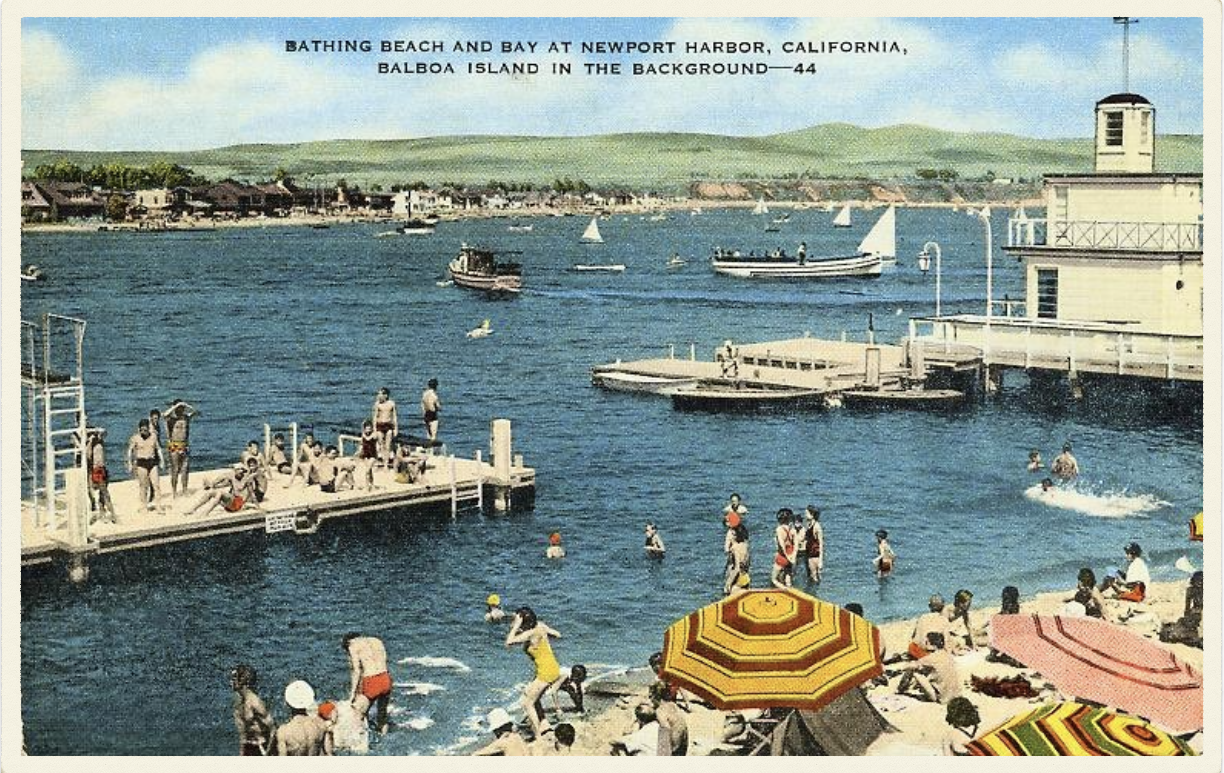

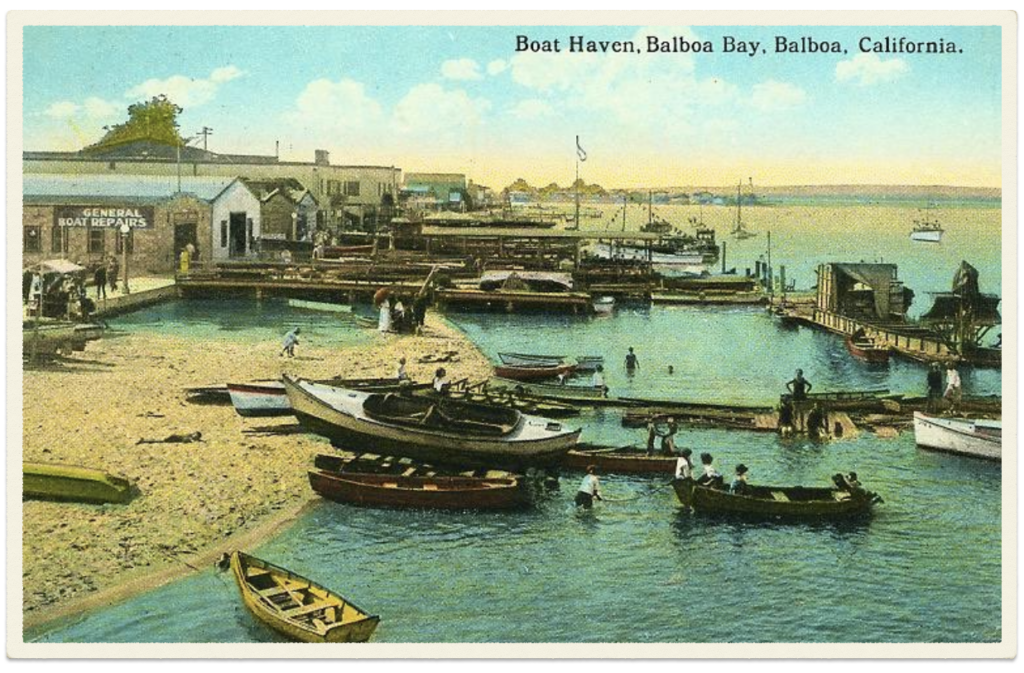

When she was five years old, in 1931, her parents, with Jean and nine-year-old brother Richard, in tow, started spending the summers on Balboa Island.

“As kids we sailed and swam and explored the beaches and played all up and down the bay and in the mud flats. Which all added up to my having an interest in and respect for our environment, and the plant and animal life, and our coastal heritage.”

Jean, her brother, and their friends’ spent their summer days with the Balboa Island Yacht Club (founded in 1922 by Carroll & Joe Beek), swimming, sailing, and playing all along Lower and Upper Newport Bay, and also exploring the beaches, mudflats, and sandbars (some of which would eventually be dredged and developed to become Harbor Island, Linda Isle, and the other Newport island communities.)

Exploring and enjoying open space, trees, blue sky, the ocean, sandy stretches of beach, playing in the waterways and channels — being a participant in our natural world — all had a lasting effect on young Jean.

In 1941, when Jean was 14, the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor and the US subsequently entered World War II. Jean’s brother, who was then 18, enlisted in the Navy. The war, Richard enlisting, and also witnessing the suffering and sickness of her mother, who struggled through her first bout of Ovarian Cancer when Jean was in high school, as well as the sudden death of her grandmother, also had a profound effect on Jean — and she decided she wanted to be of use.

Photo: Watt Family Collection

So after first studying political science and economics at Stanford, Jean decided to switch to the school of nursing, hoping to be part of the war effort. (The war, however, ended in 1945 during her first year at Stanford Nursing School.)

At Stanford Jean met her husband, Dr. Jay Watt, a resident doctor in the university’s medical program.

In 1953, Jean and Jay moved down to Newport, and together opened his practice next to Hoag Hospital, which had just opened the previous year.

They lived first on Beacon Bay and later on Harbor Island, building a home next door to her parents’ summer home — on the same lot her parents had bought for $2,500 in 1937. (You can see a photo of the Hahn Beacon Bay summer home above.)

“So we formed our own group, which is sort of symbolic of how I view politics, especially city politics. If you see something that needs to be done very often you have to do it yourself, or start it yourself. You’ve got to make it happen.”

Jean practiced nursing, supporting Jay with his practice for two years and then when she became a mother, in 1955, decided to devote herself full-time to their four kids: Tammy, Lorna, Terry and Mike. She got involved in the PTA; and when her girls needed a scout leader, volunteered, and served as a troop leader for 20 years.

In 1974 Jean and a Harbor Island neighbor were discussing the run-off and pollution in the bay after huge storms that had passed through Newport.

“We were wondering who’s responsibily it was to clean up,” Jean said. “We realized it wasn’t the HOA’s responsibility, and that the city wasn’t required to do anything about it back then. So we decided to form our own group, SPON — to help keep our bay and beaches clean. And one of the first things we did was Bay Beautiful Week, which encouraged citizens to clean up their own beaches.” Thus began 50 years of community activism.

All of us who live or grew up in Newport owe Jean a deep debt of gratitude. Without her foresight, determination, and wisdom, we would not have many of the natural spaces, parks, and so much of the beauty that we enjoy (or in my case take for granted!) today. Thank you Jean for your incredible kindness, leadership and example.

I N T E R V I E W

Cassidy: I know a little bit about your political life, that you served on the Newport Beach City Council, were Mayor Pro Tem, and Citizen of the Year in 2013. You have wonderful history in this little town… I’d love to learn more about your environmental activism and also about how you developed your sense of civic duty. Did your parents instill that in you?

The Impact of Adults Who Cared about Their Community

Jean: Oh, I think so. They didn’t become politicians or anything, but my grandfather was a state senator. My father was a lawyer. And my mother was a teacher, although she didn’t work after she got married.

And my mother was always involved in, not politics, but local groups and charities like the Red Cross. And my father, too. I grew up with parents who cared about the community.

And I was also informed by people down here in Newport. The Beek family were always very civic-minded and I spent a lot of time with them. [Joe Beek was the longest-serving Secretary of the Senate in California history, from 1919-1968.]

We started renting a house near the Beeks on Balboa Island, in the summer, in 1931, when I was five-years-old. And our families got to know one another. And the Beeks definitely had an effect on my belief that you have to be involved, and start things, and do things yourself.

A Childhood Exploring & Appreciating the Outdoors

Summers in Newport in the 1930s

Jean: Also, when we first came down to Newport, the Beeks had started the Balboa Island Yacht Club. So I spent a lot of time there learning to swim, dive, sail, and row. It was very educational and probably had a lot to do with my future.

Growing Up in Pasadena: Climbing Trees & Muddy Knees

And in Pasadena we lived in a 20-acre area and my brother and I, we played together, and we could go out every day and climb trees and dig forts and that’s just what we did. So I grew up being outdoors.

The Beeks were also quite giving. They had the yacht club right in front of their house, and it’s still going on today, right there on their family pier.

My brother was four years older and when we came down here, he sailed, so I had to crew for him. He sailed star boats, and we raced.

And the Beeks’ son Allan was my age so we played together. I remember once we collected some little yellow tickets that were floating in the bay — like the kind you might get at the Fun Zone today — and we dried them and then sold them to kids for a penny. <laughs>

As kids we sailed and swam and explored the beaches and played all up and down the bay and in the mud flats. Which all added up to my having an interest in and respect for our environment, and the plant and animal life, and our coastal heritage.

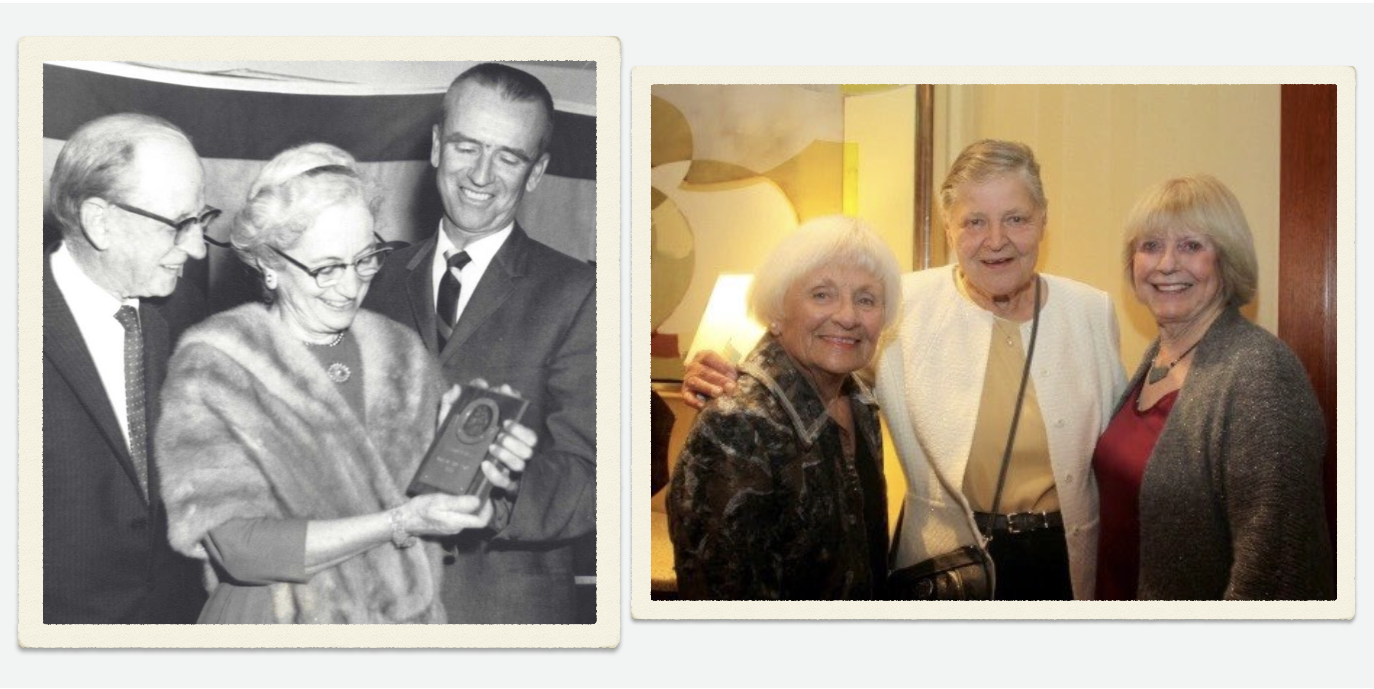

Carroll Beek’s Legacy

Photos: Orange County Register

“I took away the idea from Carroll that you can make a difference in your community.”

Cassidy: That’s wonderful. So The Beeks were were quite influential in your life?

Jean: Oh yes, very influential. There were people all along the way — everybody has people who make a difference. But Carroll Beek, she was just so committed.

I spent a lot of time with her. We would go over to their house for dinner and she always had a chalkboard up. So if any word came up that you didn’t know, she would write it on the board. She was always teaching everyone — it was constant teaching, all the time. She was very influential.

And in terms of always teaching everyone, she also, every morning, swept her sidewalk, raked her beach, and cleaned up the trash — which was unique. Most people didn’t do that unless there was a special effort to encourage them to, which we made later with our SPON organization, trying to get people to clean their own beaches.

Carroll was very active. She wrote all the thank-you notes for Hoag for a long time by hand, years ago, when it was smaller — when people would make donations.

So my takeaway from her, since I was little, was to take care of your own space and clean your beaches. And that was VERY influential in what I finally ended up doing, which actually was exactly that! <laughs> So you can see Carroll’s direct influence.

“World War II came along and we all were extremely patriotic. And all you could think about was what can I do — besides knit socks!? And so I decided I could be a nurse.”

And she certainly influenced my later years as well where I made it a point to form a continuum of non-profit organizations aimed at supporting different environmental and community causes.

I remember she got mad at me once, because I wrote a newsletter for SPON and spelled a word wrong. <laughs> She stomped her little feet and was mad at me for doing that. After all our blackboard lessons I should have known how to spell that word!

But, yes, she was a very important figure in my life. And her example, of course, was community activism. And to find ways that you that you can help.

Kate: I love that because the idea to clean your own beach and sweep your own sidewalk, in one way, it’s not that radical of an idea. But it is a really meaningful thing to do — a kind of simple thing we can do in our own personal world, or our own environment, that really has a greater impact.

Jean: Yes, exactly. It is a very simple act but it’s something we can do for our community. I took away the idea from Carroll that you can make a difference in your community.

Strive for Excellence: The Impact of Miss Erickson at Stanford Nursing School

Photo: Newport Bay Conservancy

Jean: Also, Miss Erickson, at Stanford, she was also influential — in the way I want things neat and clean.

When we went to nursing school, we had white hats, white dresses, white socks or stockings, white shoes. And she wanted everything really white! <laughs>

And when she taught us to make a bed, she wanted us to do it very distinctly and not have to be patting it down all the time. I can still remember her being so perfect.

This was in the 1940s when the nursing school was in San Francisco. It later moved down to campus in Palo Alto.

I’m fortunate in that I’ve had lots of good role models, and good sorts of people that I could interact with and remember. And they undoubtedly had an effect on me.

Growing Up in the 30s & 40s: Patriotism & a Desire to Be of Use

Kate: Also, Jean, I also remember you saying in one of the Newport Beach Historical Society interviews that the experience of your mother being sick when you were young, and then your brother enlisting in the Navy after Pearl Harbor that your response was — and that the way people thought back then was — how can I be a benefit, what can I do to help? And that’s why you decided to become a nurse. You said:

“World War II came along and we all were extremely patriotic. And all you could think about was what can I do — besides knit socks!? And so I decided I could be a nurse.”

“I grew up with parents who cared about the community.”

Jean: Well, the war, my mother having cancer my brother enlisting, it all definitely affected me. Plus the fact that my grandmother had been at our house and she was taken away one night and died from a heart attack. So I kind of gravitated toward nursing and thought that it would be useful if I could have been a nurse in the war, but the war ended the same year I started at Stanford [in 1945.]

During the war, we had a lot of patriotism that hung together. And so my experience with all of that, my response, was to try to be of use.

Shared Ethics: The Honor Code at Stanford in the 1940s

Kate: Jean, another thing I found really interesting in one of your NBHS interviews, and that I hoped you would talk about, was how important the honor code was when you were at Stanford. In the interview you said:

“The honor code was a serious matter. And the naive belief that you don’t cheat was very much entrenched in what we learned when we went to college.”

Could you talk a little bit about that? Because it’s so different from how many people think today!

Jean: Well, when I went to Stanford the honor code was a serious matter. We took pride in it — just like with patriotism. And you simply didn’t cheat.

Today people might think we were naive. <laughs> And it really is too bad. Because there’s a lot of good that comes from a shared belief. The same with patriotism, the way it hung us together. There’s a lot of good that comes from having pride in your society. In the early days everybody was on the same track.

Leadership & Supporting Roles Need Each Other

Kate: Jean, why do you think you’ve been able to accomplish so much here in Newport?

Jean: The interesting thing about what I do is really it’s leadership. There are a lot of people that want to help and will help you, but they don’t want to be the leader of a project. Or they don’t see a way to be a leader of it.

When I started to do the civic activism here in Newport, my daughter Terry, who’s an urban planner, helped me a lot — she primarily helps non-profits and cities that want to save open spaces. There’s all kinds of things you can do to be able to make a difference and get things done. And one of them is to form a non-profit so that you can raise money, and file lawsuits, if need be, and all of those sorts of things. So without her help, I probably wouldn’t have been as liable to do these things. But with her help, I’ve been able to take people’s suggestions and make them happen.

The Long-term Benefit of Citizen Activism

At age 90, in 2017, Jean — with the help of two local organizations (that she founded) and the support of thousands of Newport Beach residents — stopped a 295-foot luxury tower from being built near Fashion Island.

Jean: And sometimes it’s a wild guess if you’ll be successful or not, but you have to decide to try.

For an example, we had this luxury tower going up in Newport in a place where it wasn’t supposed to be, at the old Orange County Museum of Art property. And I talked to someone else and we decided that that if city council approved the tower going up — which would have been 295 feet and 25 stories; it would have been the highest residential tower in Orange County —, we [SPON and A Line in the Sand] would referend it, meaning we would go out and get enough signatures so City Council would have to put it to a public vote. And every time we’ve done that, we’ve won — because the people didn’t want what the council voted on, but they didn’t know what to do about it. So we did that with that proposed luxury tower project and we called it the Museum House.

So anyway, it was Christmas time, and we had a lot of nerve to do it, but we set up to do a petition referendum and went out to get the signatures.

Cassidy: How did you do that?

Jean: <laughs> Well, we have people all over town who go canvas their neighborhood and set up tables to get signatures. And it just went like wildfire. It was so easy to do. We got about twice as many signatures as we needed.

And the city council just rescinded the proposal. They didn’t even put it to a vote. <laughs>

So now it stands out as sort of a poster boy. And the city council now all come to interview SPON people to see whether they’re going get their proposals through without a referendum.

Also in 2017, Jean & friends formed a non-profit to fund & build Newport Beach’s first animal shelter for the city’s lost, abandoned & neglected domestic animals.

Jean: And then most recently I formed with others the Friends of Newport Beach Animal Shelter, which is a non-profit group. And we’ve been able to raise the money [over $3 million dollars in private donations] to build a shelter here for Newport Beach, which is interesting to me in that Newport Beach, being a wealthy city, had never done that. The city had always contracted out for their stray animals. And the animals weren’t being treated very well and were euthanized if there wasn’t room for them. And yet nobody had tried to establish a shelter here. The city council hadn’t.

So we formed our own group, which is sort of symbolic of how I view politics, especially city politics. If you see something that needs to be done very often you have to do it yourself, or start it yourself. You’ve got to make it happen.

The animal shelter is a good example of something that the council hadn’t done and didn’t have any plans to do. They call it a public-private partnership. And the good part of it is that the people in the community that care about one thing, in this case animals, they work with the city, and they provide the extra push so that the project becomes institutionalized — it becomes part of the city’s thing. And in this case we actually built the shelter and donated it to the city.

“I’m fortunate in that I’ve had lots of good role models, and good sorts of people that I could interact with and remember. And they undoubtedly had an effect on me.”

Cassidy: What spurred you to start that?

Jean: Well, that was one of those things, too, that had been on my mind — since Girl Scout leader days, actually. One year we visited a bunch of animal shelters and I was really impressed with the National Cat Protection Society in San Diego — they eventually opened one of their shelters here in Newport.

And I always thought we should have a proper animal shelter here, for all our domestic animals: cats, dogs, you-name-it. But never felt that I had the wherewithal to do it myself. And so at some point the city manager decided that it wasn’t going well with their contract — they had a contract for our animals to be taken care of at a local humane society in — I won’t name it, but the animals really weren’t being taken care of very well.

And then in 2015 the city decided to lease a place in Newport for us to have a place to put our own animals. But we always wanted to have a permanent shelter.

So at that point, I talked somebody into being president. <laughs> That’s my favorite thing to do: to get somebody else to be president. I tell them: I’ll help you. I’ll be vice president. I’ll do all the work. <laughs>

And so we formed the Friends of the Newport Beach Animal Shelter, a non-profit, and right away everybody liked the idea.

So it’s taken us five years, but we just finished raising all the money and the building for the new shelter is all but done [at a site just a few blocks down from the one the city has been leasing, on Riverside Drive]. It’s not open, but it will be by the end of the year.

And it’s a state-of-the-art shelter, something we can be proud of. And where animals will be really well cared for.

Now that was really fun to work on because it was totally nonpolitical.

Almost everybody has animals of some sort. Although I had one person who said they didn’t want to give money to animals. <laughs>

An Affordable Housing Trust: Another Citizen Effort to Help the City

“If we don’t collectively decide what we want and be able to articulate that politically and in a in a broad enough way, then we are simply at the mercy of the developers whose objective every day is to look and see what they can buy — and there’s nothing wrong with that — but they’re not going to have the community’s best interest at heart,” Jean says in one her interviews with the Newport Beach Historical Society. “Their main objective is going to be to make as much money off of it as they can.”

(Newport Beach Historical Society Interview Part 1, 21:24)

Cassidy: Thank you, Jean. I know the animals are grateful for you as well.

Could you tell me about the housing trust you’re working on now — that sounds really interesting. How did that come about?

Jean: Well, that’s another recent example, similar to the animal shelter — at the Marriott, they want to put a high rise residential building right beside it. It’s in the general plan.

And it will be big; it will be tall. And so the developers came to show me and some others at SPON their project. And I’m old enough, I can’t be the leader of a referendum at this point. It’s got to be somebody younger! So I wasn’t going do anything about it. But we talked about it and the people that are building it are local developers. And I asked them: What do you think about the current issue right now for everybody: homelessness and affordable housing. I said, what do you think about the city having a housing land trust where you get grant money, philanthropic money, and you use those funds to subsidize housing for the workforce and for the elderly who can’t afford their homes?

And these fellows both liked this and we’re now doing that: we’re forming a private, non-profit housing land trust. And so that’s the latest of our efforts on behalf of something new for the city.

Cassidy: That’s quite an achievement.

Jean: Yes, it’s a big thing. I had thought about it even before these young developers approached us — but I didn’t think I had the energy or the stamina until they came along. And now they’re funding a consultant and we’re doing that.

And, yes, the city should do that itself. But it’s not going to. So we’re going to do it anyway and have them as partners. At least that’s how it looks right now.

All Good Work Makes a Difference

Cassidy: Does it bother you — because you’ve put so much of yourself into Newport, so much wonderful time and energy — when you’re driving around now, the endless construction and that it takes forever to get anywhere? <laughs>

Jean: Well, it doesn’t bother me because I know it’s better than it could have been. Many of the things we did helped. I mean, people don’t know what it could have been, and it would have been way, way, way different. And before me, there were the Freeway Fighters.

Concerned Citizens Have Always Been Working for the Greater Good of Newport Beach

Jean If that freeway had been built in the 60s it would’ve just been horrible. It would have gone all the way down and then over Fifth Street, dividing the city and allowing big buildings and so forth.

And then the the Irvine Company planned to do commercial buildings on the coast side. So the Friends of Newport Coast stopped that and saved Crystal Cove State Beach and Park.

And then they saved even more of that area as open space. So it, it’s much different than it would’ve been. And, of course, the Upper Bay was saved, the Back Bay. Fran and Frank Robinson were instrumental in that.

And now the Banning Ranch people have saved that area. It’s 400 acres of hillsides, and it’s going to be part of the regional park over there.

So all of that combined with other things has made it not as bad as it could have been. Even though we had to fight every one of those development projects, I think the general feeling is that it’s resulted in something better.

And then there are the people who fought the airport forever. Which is something of an on-going battle!

SPON got involved in that in 1985 when they were going to expand the building. So we hired an attorney and joined the city in a lawsuit against the airport. [The airport is owned and operated by the county.] And it ended up being a settlement agreement, which keeps the noisiest planes down to a certain number.

Cassidy: It’s still pretty noisy!

Jean: Yes, but fortunately there’s a whole bunch of people focused on that. SPONs’ still a party to it. The settlement agreement went from 1985 to 2005, then to 2015. And now there’ll be another extension of the settlement.

Sue Dvorak, who I think lives in The Bluffs, she’s the one that’s working on that, representing SPON. So everybody’s doing the best they can with the airport. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than it would’ve been. So I don’t it feel bad about it. I know what could have been!

Cassidy: Well, that’s good. It really helps put it in better perspective, frankly.

Jean: And then I don’t worry about what’s going to happen. Whatever will be, will be.

A Positive Impact on Future Generations

2-3. Alma (above) & Rosaly, two of Jean’s caregivers. 3. Pink Sea Fig blooming in Newport.

4. Yarrow flowers at Newport’s Castaways Park.

Jean: One of my grandchildren, Kristina, is now living in Sitka, Alaska, and she started Friends of the Sitka Animal Shelter, up there, just like I had here.

I have five grandchildren and they’re interesting because they are all interested in what I’ve done.

Cassidy: That must be quite thrilling for you to see them taking those paths. In some ways, some of the work they’re doing is an extension of your own environmentalism.

Jean: A little bit. The one in Sitka, Kristina, she’s got a job now as statewide coordinator for ocean cleanup. She’s focused on the ocean and aquatic problems.

Cassidy: That’s a wonderful trait your granddaughter has inherited. It seems there’s a line that runs down through the generations.

Grateful for Her Family

Jean: And I’m very lucky to have my four kids. Because getting older, it’s sort of a burden. And if you can share it, you’re better off. <laughs>

And also my husband — he didn’t want to go camping with me, with my Girl scouts and all that. <laughs> But he was a really good father and his impression on our kids was good. So they all have a good work ethic and everybody’s doing well.

And my kids, they are much better off now that I have full-time caregivers — you might want to put that in your newsletter — and thank you for helping with that, because the caregivers make a big difference. They’re upbeat and they have a lot to do with our attitude so we’re very grateful.

A Good Leader Reaches Out to Others

Kate: Jean, was being in the Girl Scouts, as a troop leader, is that where you developed a lot of your leadership skills?

Jean: Through the Girl Scouts, I primarily learned about organization: how to organize and work with people.

And Girl Scouts actually got me started in the civic activism because some of my friends were working on a campaign one year. And they knew that I could organize, so they called me and wanted me to help them organize their campaign, which I did — it was a city council campaign — and they lost.

And I said, well, you can’t just jump in and expect something to necessarily succeed right off the bat. You need to have something ongoing and develop enough people to support your cause and then you can run a successful campaign.

So we started SPON in 1974, and then through SPON we had a list of people when we did other campaigns who we could contact.

“You have to look for opportunities.”

So I think it’s just that I’m willing to reach out to people. And other people are somewhat afraid of that. Or they don’t think of enough people to reach out to.

Kate: Did you always have the natural temperament to lead?

Jean: I think so. When I was little, growing up in the 20s and 30s, I didn’t have any particular activity that would’ve led me naturally towards a leadership position.

The Girl Scouts I fell into as a parent because they needed a troop leader, and I ended up being in it for 20 years. So it probably was the genesis of a lot of my organizational skills, and also people skills. And even community opportunities. You have to look for opportunities.

Somebody said to me the other day: What’s your next thing going be that you start and make finish? I don’t know. I can’t think of anything right now. But usually I was able to think of something that needed to get done and then you reach out. The best example of that recently is the animal shelter.

Advice to Younger Generations

Just do what you can do. Don’t dwell on the direness of anything, but do what you can do and then remember to also enjoy your life.

Kate: Jean, do you have any advice for young people who feel very discouraged about the environment, or the way the world’s going? How do you not lose hope?

Jean: The only advice I have is just pick something that you can help with and do it. That’s what I do.

And my grandchildren, they’re very thoughtful, and I think because they’re focused on something they can do, they don’t get discouraged.

I had a friend, Sherry Rowland, who discovered the ozone hole. At the time — this was in the 70s — there was discussion that if we didn’t do something about the ozone and CFCs, then in 50 years we weren’t going to be able to control it.

So I asked his wife how they dealt with that, knowing that it was really dicey. And she said, well, he just did what he could do and then they enjoyed life otherwise. <laughs>

So you just do what you can do. Don’t dwell on the direness of anything, but do what you can do and then remember to also enjoy your life.

A friend was here for lunch the other day with a few others, and one of them was talking about all the world’s problems. <laughs> And my friend said she just doesn’t worry. And it’s interesting because she has colon cancer, and she’s been going to the City of Hope, and she has been taking something but it doesn’t make her feel bad. So she looks good, she feels good. She’s about 87, I think. And she said she doesn’t worry about anything because why worry about anything that you can’t do something about? <laughs>

So I think: I’ll try and take a page out of her book. <laughs>

Attitude Is Everything

Photo: Watt Family Collection

Jean: Attitude is everything. When I got into all this with the oxygen, my attitude could be pretty bad. So Lorna, my daughter, said there’s this exercise called Three Good Things. In fact, this is interesting too, because the whole country is a little bit focused on health, healthy communities, and mental health right now. They’re doing a lot more for mental health these days. And one exercise you can do is the Three Good Things.

So in the morning, instead of thinking, Oh my gosh, I’ve got to go through all this stuff again — the oxygen, the wheelchair, the challenges of aging, you name it, whatever myself or others are going through — you think of three good things.

So I started doing that exercise and then I would focus on: What’s good about this day? And of course there are good things. I actually put it on as a journal on my computer. I put the date and start with three good things, typing them out. And it makes you think about what is good instead of just dwelling on whatever isn’t and that you can’t change anyway.

Kate: It reminds me of Carroll Beek’s example of cleaning her own beach. Something that’s kind of simple but actually has a profound effect.

Jean: Yes, it is. And it certainly can’t hurt if you focus your mind on what’s good instead of “I just really don’t like this situation.” <laughs> Believe me, I could go there any minute of the day, but there is no use for that, you know. It just doesn’t help me any. <laughs>

Dealing with the Physical Limitations of Aging

6. Pink orchid rockrose above the Bay Bay.

Cassidy: Growing older and the problems that come with age, the physical limitations, do you find that really frustrating?

Jean: Yeah! That’s what the Three Good Things are for. Because it is really frustrating. Because you want to do all kinds of stuff.

But then I look at the bright side — whatever that is — because I am enjoying lots of things. I’ve been having people over for lunch and seeing friends. And because I’ve been doing all these non-profit groups over the years, I know a lot of people who are younger and so I get to see them and even participate in some of their projects.

And then because they’ve made it so easy for people like me with wheelchair access. And then my oxygen, I’ve got the little purse thing, so I can go to a meeting or out to see people. I can do all that. I don’t think I would have been able to before the American Disability Act, but with all the equipment we have now and with the requirement for access, we can do almost anything. You just have to be willing to go out and do it.

Continuing to Love & Be Nurtured by Nature

“I grew up being outdoors.”

Cassidy: Were you brought up with any religion?

Jean: Not really. And I feel kind of lucky about that, too, because I’ve never had the any of baggage that can sometimes come with a religious upbringing, which I consider to be a very big benefit. But I don’t have a problem with religion at all. I’m not anti-religion.

And I will be forever grateful for my family for not making religion a thing that I had to do because of them. It was totally my choice.

Neither of my parents were religious or my brother. I wouldn’t say they were atheists, but agnostic. Neither of my parents went to church.

We had housekeepers growing up and they took me to the Baptist church and the Lutheran church. So I got a lot of church going, but it wasn’t from my family.

And my husband’s family were Mormons. So I figure they’re praying for me. <laughs> They always do. One of the younger generation from my husband’s family calls me. The Mormons always watch out for their people. They’re very good about that.

A local church had an ecology day recently, and they invited me to be on a panel. I had lunch with the minister, and he said, Do you go to church on Sunday? And I told him no. <laughs> And he said, What do you do? And I said, I garden. As far as I’m concerned, a garden is just as much a shrine as anything.

0 Comments