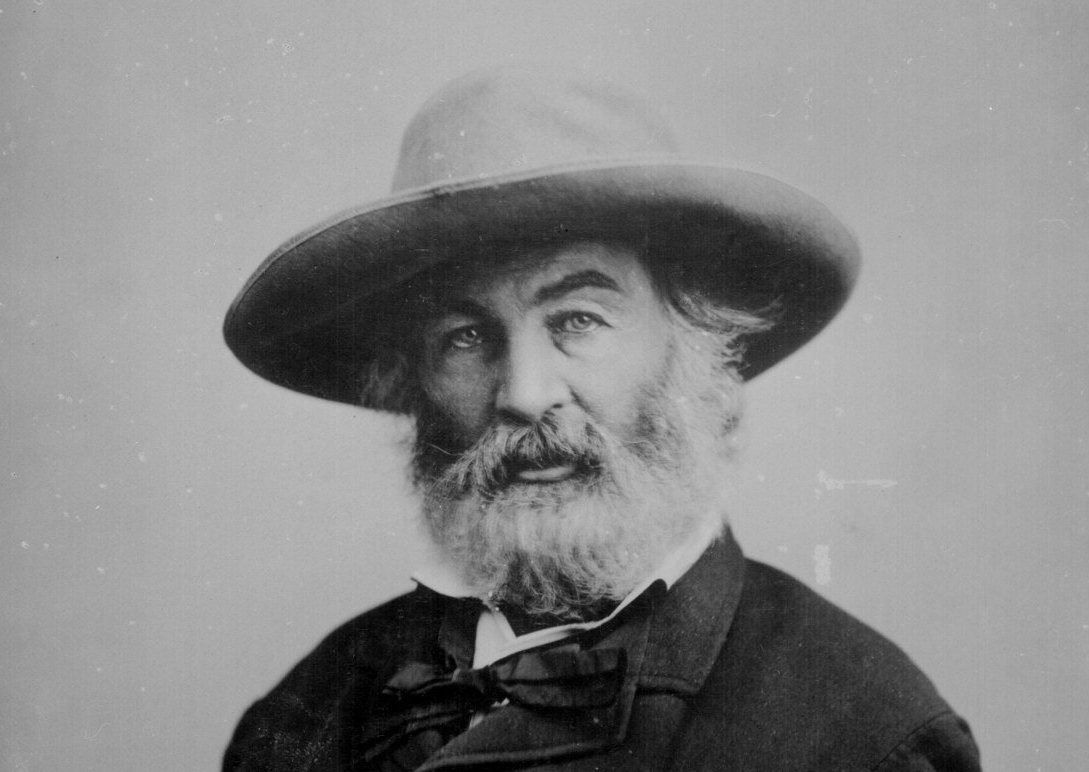

Walt Whitman (1819–1892) was born May 31, 1819 into a working-class family in Long Island, New York. He worked throughout his life as a teacher and in the publishing and printing trades. Whitman also served as a nurse during the American Civil War, 1861–1865, which he said, offered him “the greatest privilege and satisfaction . . . and, of course, the most profound lesson of my life.”

He tended to tens of thousands of wounded Union and Confederate soldiers, nursing them, helping them write letters, bringing gifts.

An excerpt from “Walt Whitman” by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price:

“Whitman had in fact been visiting Broadway Hospital for several years, comforting injured stage drivers and ferryboat workers (serious injuries in the chaotic transportation industry in New York at the time were common). While he was enamoured with the idea of having literary figures as friends, Whitman’s true preference for companions had always been and would continue to be working class men, especially those who worked on the omnibuses and the ferries (“all my ferry friends,” as he called them), where he enjoyed the endless rhythms of movement, the open road, the back-and-forth journeys, with good companions. He reveled in the energy and pleasure of travel instead of worrying about destinations: “I cross’d and recross’d, merely for pleasure,” he wrote of his trips on the ferry. He remembered fondly the “immense qualities, largely animal” of the colorful omnibus drivers, whom he said he enjoyed “for comradeship, and sometimes affection” as he would ride “the whole length of Broadway,” listening to the stories of the driver and conductor, or “declaiming some stormy passage” from one of his favorite Shakespeare plays.

“So his hospital visits began with a kind of obligation of friendship to the injured transportation workers, and, as the Civil War began taking its toll, wounded soldiers joined the transportation workers on Whitman’s frequent rounds. These soldiers came from all over the country, and their reminiscences of home taught Whitman about the breadth and diversity of the growing nation. He developed an idiosyncratic style of informal personal nursing, writing down stories the patients told him, giving them small gifts, writing letters for them, holding them, comforting them, and kissing them. His purpose, he wrote, was “just to help cheer and change a little the monotony of their sickness and confinement,” though he found that their effect on him was every bit as rewarding as his on them, for the wounded and maimed young men aroused in him “friendly interest and sympathy,” and he said some of “the most agreeable evenings of my life” were spent in hospitals.

“By 1861, his New York hospital visits had prepared him for the draining ordeal he was about to face when he went to Washington, D.C., where he would nurse thousands of injured soldiers in the makeshift hospitals there. Whitman once said that, had he not become a writer, he would have become a doctor, and at Broadway Hospital he developed close friendships with many of the physicians, even occasionally assisting them in surgery. His fascination with the body, so evident in his poetry, was intricately bound to his attraction to medicine and to the hospitals, where he learned to face bodily disfigurations and gained the ability to see beyond wounds and illness to the human personalities that persisted through the pain and humiliation. It was a skill he would need in abundance over the next three years as he began yet another career.”

In 1855 Whitman published the collection of poems Leaves of Grass, which the American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson called “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom America has yet contributed.” Whitman continued to rewrite, refine, and republish Leaves until his death in Camden, New Jersey, March 26, 1892.

I have always loved Whitman’s poem, “Miracles.”

“Miracles” by Walt Whitman

Why, who makes much of a miracle?

As to me I know of nothing else but miracles,

Whether I walk the streets of Manhattan,

Or dart my sight over the roofs of houses toward the sky,

Or wade with naked feet along the beach just in the edge of the

water,

Or stand under trees in the woods,

Or talk by day with any one I love, or sleep in the bed at night

with any one I love,

Or sit at table at dinner with the rest,

Or look at strangers opposite me riding in the car,

Or watch honey-bees busy around the hive of a summer

forenoon,

Or animals feeding in the fields,

Or birds, or the wonderfulness of insects in the air,

Or the wonderfulness of the sundown, or of stars shining so

quiet and bright,

Or the exquisite delicate thin curve of the new moon in spring;

These with the rest, one and all, are to me miracles,

The whole referring, yet each distinct and in its place.

To me every hour of the light and dark is a miracle.

0 Comments