My father-in-law liked to read, eat sweets and drink whisky. Most of all he liked to make money. He had an unconscious habit of shaking coins in his hand–a reminder? My mother-in-law used to call him moneybags but that was after they were divorced. Mr. Mac, as I used to call him, followed his mother’s maxim, “If money is the root of all evil, give me more of the root.”

He did focus on that golden root perhaps so tenaciously because his Scottish parents not only had little fortune but because his mother taught him the value of frugality. Whenever he had finished his whisky bottle, he poured a little water in, swirled it around and sloshed his glass with the last wee dram. Despite his collection of first-class free airplane socks, he continued to wear old socks with holes. He would drive his luxurious Jaguar like an army jeep across potholed farm roads and with his unbothered spaniel Sandy riding in the boot. Although careful by nature, Mr. Mac was incredibly generous, never tight-fisted. When I arrived in Cape Town newly married, he gave me his Mercedes sports car without a second thought.

On his South African farm he taught me to fly fish for trout. On our way back to the White House (the farm house) he invariably proclaimed, “You’ll sleep well tonight,” his platitude for the reliable result of country air mixed with a drink or two. By bedtime we were as “dim as a Toc H lamp,” one of his Christian Science mother’s expressions he kept for the slow-witted.

Some wonderful times were evenings with Mr. Mac and his veteran friends on the farm recounting war exploits. Mr. Mac loved telling of his parachuting into Yugoslavia with his volume of Shakespeare and silk pajamas. His first night on the ground, he took his boots off to sleep, a mistake he never made again.

After the war, Yugoslavia stayed with him. He kept up with his Slovenian bodyguard, Carlo, and his family. He introduced his own family to them and Yugoslavia with many trips there. He also taught me about The Special Operations Executive (SOE) in the Second World War. He read everything he could about the war besides donating to an historian his own diaries from his SOE activities in the Balkans. He loved fact and I loved fiction, but the war reading he introduced to me – the SOE activities such as “Ill Met by Moonlight” by Billy Moss – read like fiction they were so exciting and dramatic–all the more extraordinary, being real and true.

The war was an important part of his life. In London he was a member of the Special Forces Club in Knightsbridge where he would meet some of his cronies such as Peter Kemp and Reg Hibbert. He always stayed there when in London. He told me about a memorable lunch, noon to five, in Rome with Peter Kemp who had fought for Franco in the Spanish Civil War and had Franco decorations he would flaunt to the Albanian Partisans, many of whom had fought in the International Brigade and this would infuriate them. The politics of the Balkans during the Second World War is confusing, yet in a word it was anti-German. What is clear from my father-in-law was his love of the people there and the courtly hospitality shown the soldiers in those remote mountains where a visitor would be fed first before family and where strict codes of personal honor prevailed.

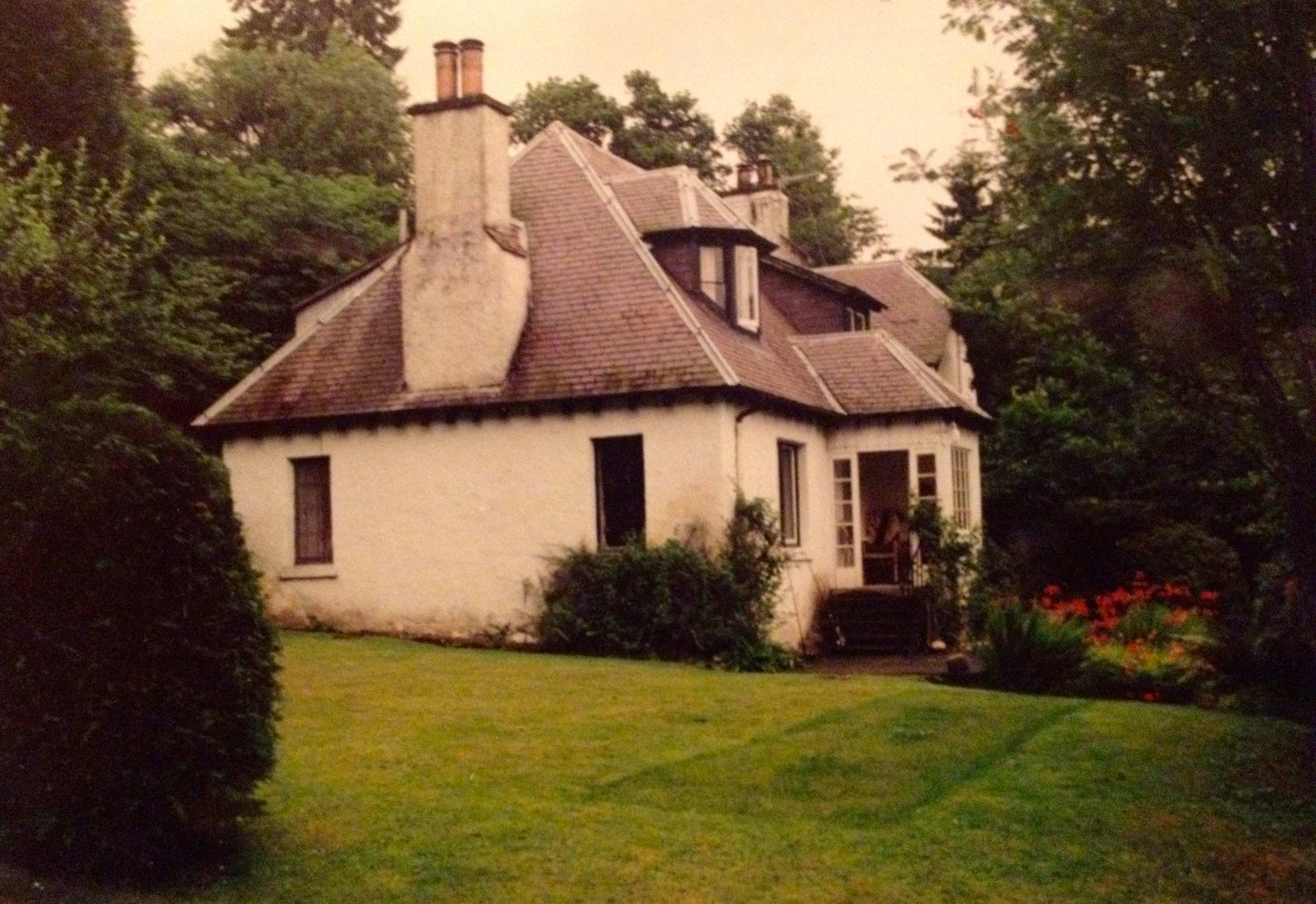

Central to Mr. Mac’s heart was his love of Scotland, his birthright. When he was able, he bought a house in Scotland and lived at Kindrochet part of the year. Through his generosity and open-door invitations to Kindrochet, many people have discovered Scotland’s inner beauty, “annihilating all that’s made to a green thought in a green shade.” (Marvell)

When his son was capped for Scotland in rugby, Mr. Mac couldn’t have been more elated. He accompanied me to all the matches from London to Paris, Dublin, Cardiff and Edinburgh. We never forgot our flasks (for the nerves). Once in Edinburgh, we inadvertently ended up in the same hotel as the team, the Braid’s Hill, and had to watch our step as the players were meant to be secluded before games. If we passed them in the lobby, we just kept walking and then laughed about it later over a drink.

After his son’s first match for Scotland against England, Mr. Mac escorted me to the London ball (there was always one following each International). He left the taxi running as he walked me to meet his son and got so involved talking to all of the players that he forgot about the taxi altogether–over a hundred pounds later!

Rugby ran through Mr. Mac’s life as his sons excelled at the sport. Besides two Internationals, all three of his sons are blues, having played for Oxford against Cambridge. My first encounter with rugby and Mr. Mac was at Oxford and the Varsity match, Oxford vs. Cambridge. On a baltic first Tuesday in December, we met in the mud of Twickenham’s carpark. From the back of the boot of his silver blue Rolls, we drank pre-game champagne and picnic’d on Fortnum & Mason delicacies, not to mention Melton Mowbray pork pies and other delicacies from Harrod’s food hall. We had a first-class time, first-class being one of his favorite epithets.

Further down the road in his Rolls, Mr. Mac gave his youngest son, Coll, and me a tour of central Scotland’s fog. Literally, that’s all we saw besides chimney smoke beckoning us to a pub’s lunchtime pink gin, his preferred lunchtime tipple.

Mr. Mac’s parents were from Iona and Mull. We ferried the clear waters to Iona to see what was left of the original croft and to read the gravestone in the Cathedral cemetery acknowledging the nine Macdonald sons born there. Mr. Mac’s mother, Catherine MacKinnon, was from Mull and on her deathbed said, “I am looking up Loch Scridain to Ben More.” It’s interesting that her final view was toward the Munro, Ben More, rather than the opposite view, equally wonderful across the loch and the Atlantic to the Isle of Staffa. She often said, “When I was young I was so strong and so happy I could skip from Bunessan to Pennyghael and back.”

It was she who took her two children, Donald and Catriona, from Liverpool to live in Durban, the South African port where the children might see more of their seafaring father, Dugald. Donald, or Mr. Mac, was fifteen and began work in Durban to help support the family, finishing his education at night school. He worked hard and enjoyed well. Education ranked highly with him. He paid for his children and some of his grandchildren to go to the best private schools and universities.

Kippers for breakfast, oysters and champagne for brunch, I imagine he’s bringing in the gloaming to the sound of the silvery Tay and salmon running, a dram of the Famous Grouse on his left and a bucket of Quality Street within reach to his right, not having to get up in the night to find it in the dark.

Further Reading

- Iona Abbey

- Special Operations Executive, World War II from Wikipedia

- BBC History ~ Partisans: War in the Balkans 1941-45

-

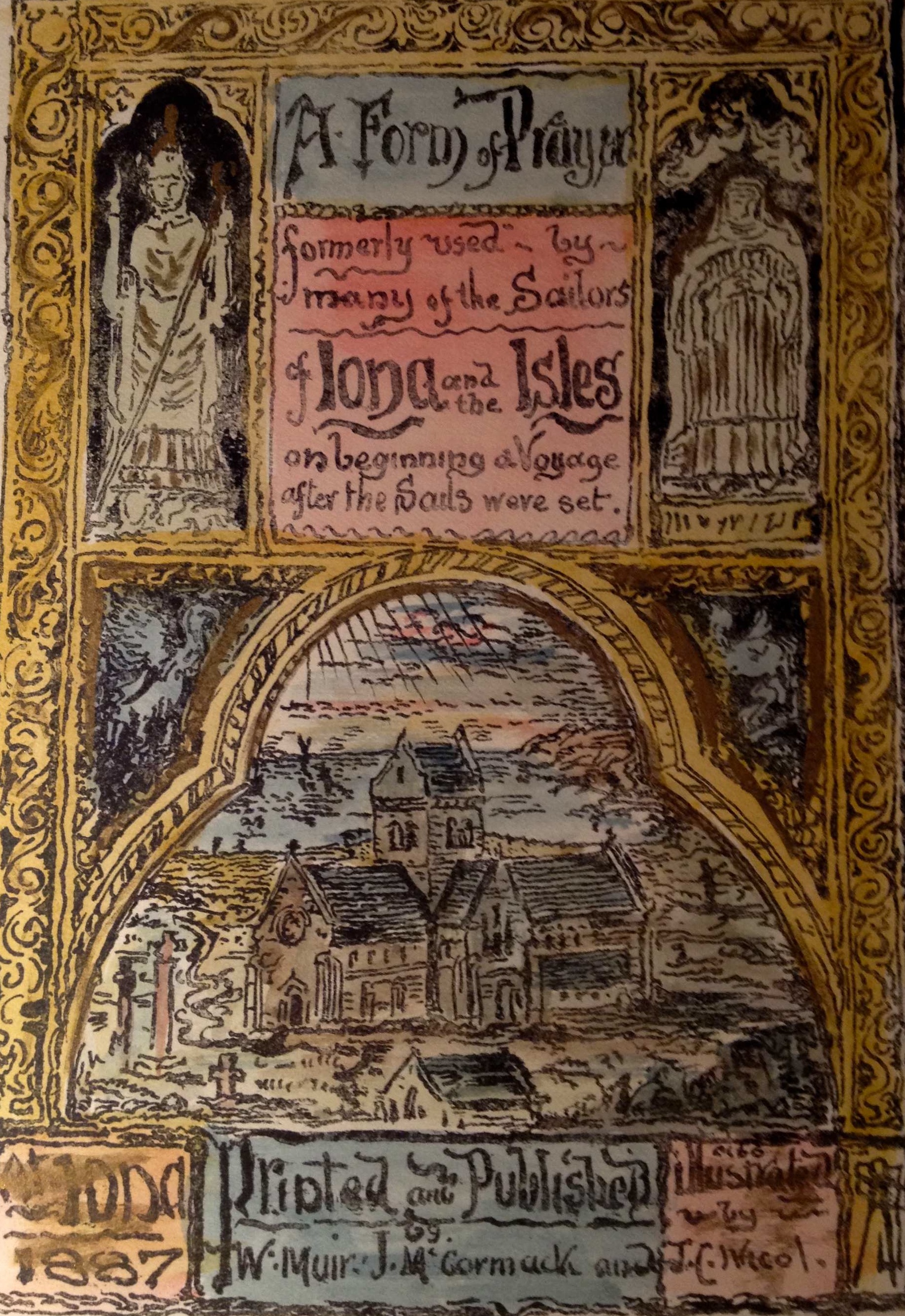

From "The Blessing of the Ship," Iona, 1887.

-

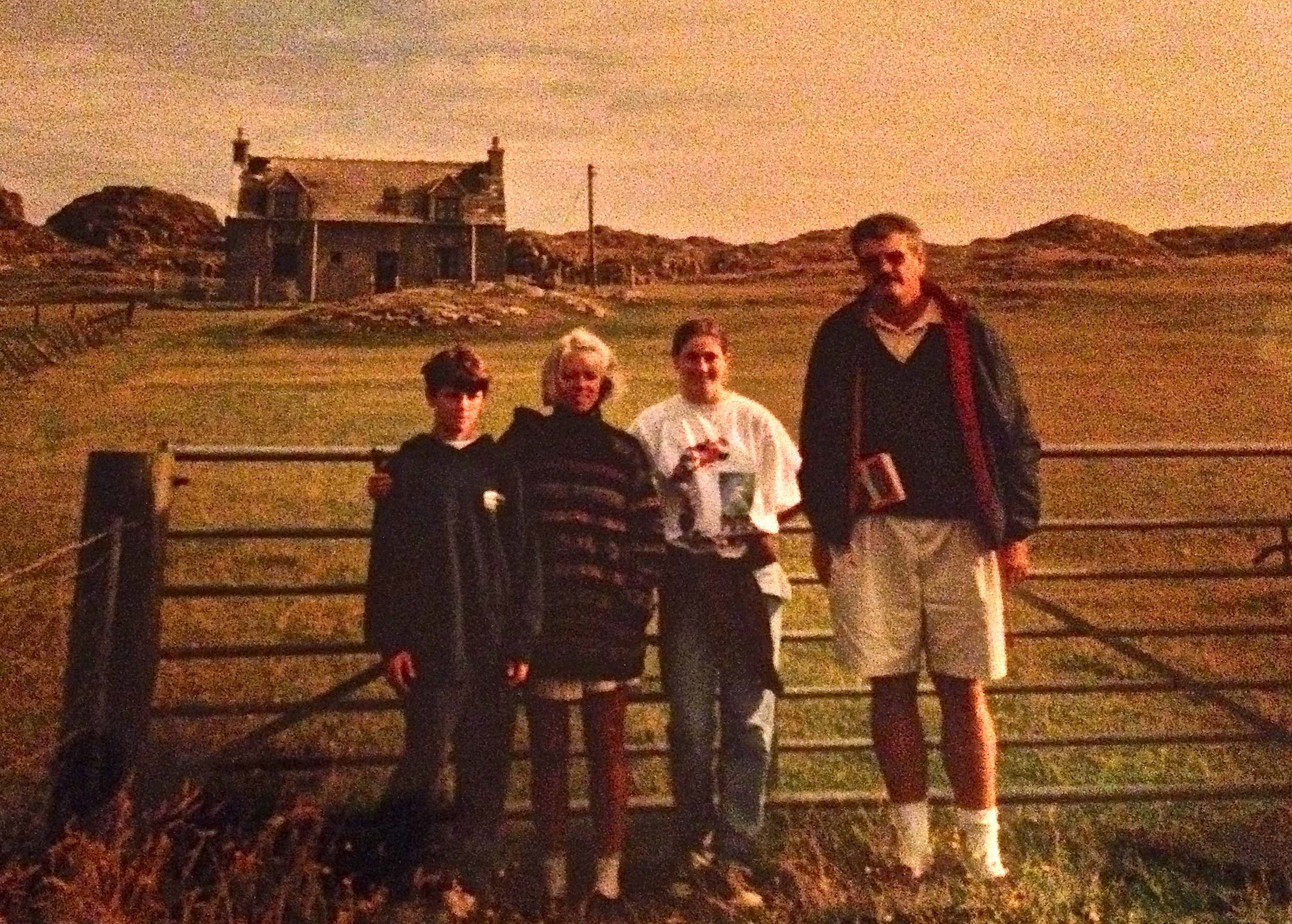

"Machir," Macdonald family croft on Iona in background.

-

Donald & Catriona

-

Mr. Mac, Coll, Julia at Varsity match pre-game.

-

Donald, to the left.

-

Young Donald.

-

With Kate and Inney.

-

Kindrochet

-

Donald, Catherine MacKinnon Macdonald, Catriona

-

Mr. Mac, man of business, at 3 Green Street, Cape Town.

-

Donald, center, in the mountains of Macedonia during World War II.

-

Mac's SOE: Chiddy, Thornton, McKenzie and himself at center.

-

At Twickenham.

-

Setting off for the Garden Route from Cape Town to Durban and Julia's wedding in 1978. Mr. Mac, Lizzie, and me.

-

Mr Mac with his nine grandchildren.

0 Comments