“I see America, not in the setting sun of a black night of despair ahead of us, I see America in the crimson light of a rising sun fresh from the burning, creative hand of God. I see great days ahead, great days possible to men and women of will and vision.”

― Carl Sandburg

I have loved getting to know our friend Doris Felman and learning about her life — hearing her stories of growing up with her three siblings in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh; about the incredible education she received there, sparking and nourishing a lifelong love of learning; about her industrious professional life and accomplishments and careers — from nuclear scientist to provisional math teacher to real estate agent and broker to substitute teacher to lawyer; about her deep commitment to and love of her family; and her life-long appreciation and love of art, architecture, and music.

Doris has an incredible mind and memory — at 93 she can recall dates, facts, and stories from growing up in Pittsburgh in the 1930s and 40s as if she were describing events that took place yesterday.

She’s also a natural teacher and polymath.

Through our conversations Doris introduced me to the great American workingman’s poet Carl Sandburg; taught me about the life of Marc Chagall, one of her favorite artists, who painted the dreamlike ceiling of the Paris Opera House; explained to me in laymen’s terms how they tested the nuclear reactors that fueled the USS Nautilus (the world’s first nuclear submarine — Doris was part of the selective team of scientists and engineers who developed the Nautilus in the 1950s); about imaginary numbers; constitutional law; the architecture of Richard Neutra and Frank Lloyd Wright; the magic of symphony music; and more.

A love and dedication to family is apparent in any conversation with Doris.

“Every day that you live, no matter how you live, it’s precious with you and your family and your relatives,” she told me.

Doris shared many kind and endearing anecdotes about her siblings, her children, mother, grandchildren, nieces and nephews, and her beloved husband Dick to whom she was married for 46 years:

“He had the best heart and he had this wonderful sense of humor and a sense of adventure. That made my life exciting.”

Beginnings — Pittsburgh

Doris was born on July 19, 1928 at Pittsburgh’s Magee-Woman’s Hospital, the first all-women’s hospital in the United States. She was the second of what would be four children born to Freda and Irwin Mattes, who were both from Eastern European Jewish families. Freda was born in the US — her parents came to Pennsylvania from Galicia in the former Austria-Hungarian empire where her grandfather had been a rabbi; and Doris’s father, Irwin, emigrated from Belarus.

The Squirrel Hill neighborhood in Pittsburgh where Doris grew up has been the center of Jewish culture in the city since the 1920s, with one of the largest Jewish communities between New York and Chicago.* It is one of Pittsburgh’s most vibrant neighborhoods.

“Pittsburgh is an incredible city because it’s the gateway to the Midwest,” Doris says. “So it has a lot of the characteristics of Midwestern people, which is different than the filtered culture in the Northeast or on the West Coast. Carl Sandburg, the poet, really captured what Midwestern culture is like.”

* (“History of the Jews in Pittsburgh,” Wikipedia; “This is Squirrel Hill: How One Neighborhood Became Pittsburgh’s Center of Jewish Life,” Rossilynne Culgan for The Incline. October 29, 2018.)

A Devastating Loss

Tragically, in 1936, when Doris was six-years-old, her father died suddenly, devastating their young family. Doris’s older brother was eight, her younger sister five, and her youngest brother only three-years-old.

Her mother, Freda, worked all sorts of jobs to support their family, including running a variety store on the main street in Squirrel Hill and later in south Pittsburgh, where Doris would take two street cars and a bus after school to help her. Freda also worked as a Metropolitan Life Insurance agent during World War II.

“All the men were overseas, so they started hiring women,” Doris said. “And she walked her beat knocking on doors, selling life insurance. Can you imagine? In the middle of Pittsburgh winters, in the rain and snow, there she is outside knocking on doors.”

It was important to Doris’s mother that her children were exposed to culture, music, and art.

“My mother was an amazing woman,” Doris said. “She never gave up on making sure we all had not just an education, but we had music and dancing lessons. She was incredibly interested in all of the arts and music.”

After school Doris and her sister, Aileene, took dance lessons at Gene Kelly Studio, which was in their neighborhood on Beacon Street — Gene Kelly was a fellow Pittsburgher and had a special relationship with the Squirrel Hill Jewish community. He got his start teaching dance classes for Congregation Beth Shalom.

“My sister learned ballet, and I was a tap dancer. If I could still dance, I could still do Gene Kelly’s tap routines.”

All of the Mattes siblings took music lessons. “My older brother played the cello in the school orchestra and I played the French horn,” Doris said. “We all had music and singing lessons. We were poor, but we had a very, very rich art’s culture.”

Doris lovingly remembers learning the songs of the great American folk composer Stephen Collins Foster in her third grade music class.

Every Sunday Doris and Aileene would take the street car to the Pittsburgh Symphony at Syria Mosque where their aunt worked and they were given free admission. “With the symphony you get exposed to really beautiful music, beautiful classical music,” she said. “And there’s no substitute for that kind of exposure to culture.”

Doris’s aunt would also take her and Aileene backstage to meet the conductors. Once they even met the famous Hungarian conductor Fritz Reiner who was music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra from 1938-48.

Their aunt was, in fact, the executive secretary for the manager of the symphony. Before her father died, Doris’s parents had paid for her aunt to attend what was then the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon). She was the first person in their family to go to college and majored in secretarial sciences, one of the few baccalaureates for women then.

“We were poor, but we were intelligent, and educated,” Doris said.

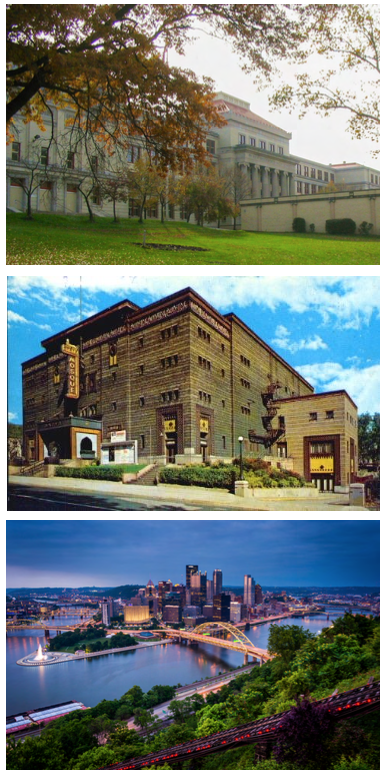

From top: Taylor Allderdice, where Doris went to high school in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh; Syria Mosque, the heart of Pittsburgh’s music culture for 75 years, and where Doris and her sister Aileene attended the symphony every Sunday; an evening view of Pittsburgh from the top of the Duquesne Incline in Mount Washington.

The Only Girl in Hebrew School

Doris’s mother got special permission for Doris to attend Hebrew school when she was eight-years-old — when learning Hebrew was a boy’s-only-club. “Mother knew she needed to keep me busy,” Doris said. “The rabbi lived across the street from us, and he and his wife were the only ones when my mother was working to have any influence on us.” So Doris studied the Torah and learned Hebrew along with the neighborhood boys who were preparing for their Bar Mitzvah. “I was the only girl, and the only way the teacher could control the boys was by throwing blackboard erasers! All I could do was duck. Imagine that.”

Doris believes learning Hebrew played a significant role in preparing her mind for higher math in high school and college. (She also has a theory that the reason there have been so many award-winning Jewish mathematicians is because they would have learned Hebrew when they were children.)

“Hebrew is a language with different symbols,” she explained to me. “And so you have to relate those symbols in order to express yourself in Hebrew words. And that’s the same thing with higher math — higher math is a language. And that’s what you learn: you learn the relationship between words and imaginary numbers. It’s the same thing, a visual thing.”

An Enlightened Education

Doris’s receptive mind thrived in the educational environment of the Pittsburgh public school system, which provided a broad education and nourished children’s talents, she says. The elementary school she and her siblings attended, for example, recognized Aileene’s artistic talents and organized for her to go on Saturdays to Carnegie Mellon where she learned to sketch from live models — the same program Andy Warhol attended. “She was incredibly talented,” Doris says. Aileene went on to study fine arts at Carnegie Mellon on a scholarship.

Doris credits Taylor Allderdice High School in Squirrel Hill as laying the foundation (along with her mother) for her and her siblings to achieve so much educational and professional success. Allderdice was ranked one of the top ten high schools in the country according to a study done at Carnegie Mellon, Doris told me. “Why? Not because we had superior students, but because there was a milieu of students, a milieu of all the cultures,” she said. “There were 3,500 students and it was one of the first high schools that bused in steel workers children from across the river, from the very famous Homestead Steel Works.” Allderdice provided a broad range of educational opportunities for all types of students, including academic, vocational, or business diplomas, and there were special programs for gifted students.

“My algebra teacher was the most incredible teacher of algebra that you could possibly imagine,” Doris said. “He created such an enthusiasm for algebra and imaginary numbers. Dr. Wagner loved teaching and he would go around and have children learn how to think with imaginary numbers. That’s what algebra is. And it’s a very good basis for learning languages.”

Doris excelled in math and chemistry and won a Westinghouse Science Talent Search award based on qualifying test scores and submitting a project using electrolysis to determine the atomic weight of copper. She graduated in the January 1946 class at Allderdice.

She attended the University of Pittsburgh on two scholarships and graduated with double majors in chemistry and math.

It was important to Doris to stay close to her family where she could continue to be a support to her mother and younger siblings. Like her mother, Doris was industrious. “When I was in high school I always had a job, always,” she said. She recalled the summer she was 16 and worked as a playground leader for a school in the Polish neighborhood on the north side of Pittsburgh.

“I applied to the Pittsburgh Public School offices in the Frick building across from Pitt campus for a summer job. The assignment was at an elementary school on the north side of Pittsburgh across the Allegheny River Bridge. It was a neighborhood of poor Polish residents who worked while their children were not at summer camps. I had to take two street cars and a bus every day and bring out all the equipment and entertain those children with whatever I could figure out to do to keep them busy when the families were working. This was a challenge!”

At the University of Pittsburgh Doris took every chemistry course she could take, spent hours in the lab, and worked as secretary for the assistant head of the department.

“I graded papers for Dr. Hugh Safford,” she said. “I needed money and Pitt had a little cafeteria called the Tuck Shop on campus and for 20 cents you could heat up a can of Heinz soup and that would be my dinner. And many times I would walk home from the university through Schenley Park to save money on carfare because I went there by streetcar. That was my challenging life, but I did not feel deprived. I felt so lucky to be able to do all the things that I did and it was much more interesting than just being a student and going to class and then coming home.”

During college Doris also took summer jobs, including working for the US Bureau of Mines in Pittsburgh; for the Hagan Corporation testing Hobart electric dishwashers (which make Whirlpool) using Calgonite; and as a quality chemist for Heinz Company in Ohio where she tested their ketchup to make sure it didn’t have too much or too little mold before bottling. “All Ketchup has mold in it,” Doris explained to me. “And the amount of mold in it makes the quality of the Ketchup.”

At Pitt she also fell in love with her husband Dick. He was in the previous graduating class from Allderdice and was working at his family’s industrial linen business. “I found out while attending Dick’s high school class reunion that he was very popular with this female classmates because he was the only student with a car, a red convertible, unique in the 1940s.”

“As a Pitt student, most of the time I studied in the university library and spent many nights studying for my classes. Dick would come by in a laundry delivery truck with dirty laundry and no seats, and I would sit on the dirty laundry and he would take me home.”

USS Nautilus

In 1958, after her first two children Ira and Jacalynne were born (in 1951 and 1953), Doris was hired by Westinghouse Electric Corporation at a remote site outside of Pittsburgh, the abandoned first Pittsburgh Airfield, identified as the Bettis Atomic Power Lab. Westinghouse had been selected by the US Navy to create and build the world’s first safe nuclear-powered submarine. Doris joined the team of scientists that designed and directed the construction of the nuclear reactor and propellant system of the nuclear submarine. The program was under the supervision of Admiral Hyman Rickover, a Polish-born engineer (when Poland was part of Russia), who joined the program in 1946.

“I was a chemist and had the academic expertise,” Doris said. “I also had a lot of experience, hands-on and education-wise to be able to do the job.”

Doris was the only woman on the Nautilus team. I asked her if the men she worked with were ever dismissive of her or if she has to work twice as hard to prove herself.

“I just did my job,” she said. “I was very well-respected. But it was also a very lonely life. My husband was very practical and always said, you do just do your work. I also was lucky in the sense that this was a unique experience for a woman at that time. I wasn’t the top of the department, but I had a lot of responsibility.”

Doris took copious notes of all their work and published the complete record.

She explained to me that the time spent from 1957-59 to develop a safe nuclear-powered US submarine was motivated by the discovery of a torpedo-loaded diesel powered German submarine sunk off the Atlantic Ocean coast of New Jersey after WWII in the 1950s.

“[The] Nautilus would go on to claim numerous records and world-firsts, its onboard nuclear plant delivering capabilities far exceeding what had gone before,” writes Andrew Wade in April 1954: The World’s First Nuclear Submarine for The Engineer. “It’s level of performance effectively rendered obsolete the anti-submarine warfare that had evolved during the war.”

Doris and the Westinghouse scientists forever changed the field of nuclear engineering.

Teaching at Allderdice

In 1959, while her husband was out in California starting a new business, Doris got a provisional certificate to teach math at Allderdice.

“I really wanted to teach because I feel the only way to get students to be curious to learn is to help them learn and reason,” Doris said. “That’s what a scientist is — somebody that reasons from facts and maybe comes to some conclusion that will be helpful.”

It was the same fall that Nikita Kruschev famously visited the US — the first Soviet premier to visit the United States. On September 24, 1959, Kruschev toured Pittsburgh, which took him down Beachwood Boulevard, right next to Allderdice.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, right, with U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower riding in car in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 15, 1959. Associated Press.

“I remember seeing his bald head,” Doris said. “It was a nice day and Kruschev drove by in an open convertible. I saw him, my class saw him. They wouldn’t understand the universal significance of Kruschev today. He wanted to come to Disneyland — I heard this on the news — and they wouldn’t let him because they thought maybe he would learn some secrets from the Disney submarines!”

A Cross-country Move & Career Changes

Later that year Doris and Dick and their two children moved cross country to California in their Ford Skyliner hard-top convertible. They lived first in Beverly Hills, where Doris obtained a real estate broker license, and five years later settled in Orange County. Doris updated her provisional teaching credential from Pennsylvania by attending classes in probability and modern algebra to obtain a life credential from UCLA to teach mathematics, chemistry, physics and languages in high schools in California.

While working full-time as a substitute teacher she attended Pepperdine Law School’s Orange County campus at night. Doris was selected for the staff of the inaugural law review — a requirement for the law school to receive accreditation from the American Bar Association. She edited and published the first edition of the Pepperdine Law School Journal, and also wrote a casenote commenting on the per curiam opinion of US Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist in California vs LaRue 409 U.S. 109 (1972) in Pepp. L. Rev. Issue 1 (1974).

Doris’s casenote was cited in a subsequent written opinion of Justice Rehnquist’s in US Postal Service v. Greenburgh Civic Association 453 U.S. 114 (1981), a confirmation of the scholarly content of the first Pepperdine Law Review.

“There’s nothing mysterious about law,” Doris said. “Like math and physics and chemistry, it’s just a way of thinking. And many people who major in psychology make very good lawyers because it’s a rational way of thinking.”

Doris graduated in 1974 and went to work for the Legal Aid Society of Orange County, founded by local lawyers so that low-income individuals could also receive free legal services. This was important work, Doris said, but also was actually accessible to women. “It was the only job I could get,” she told me. “They wouldn’t hire women then.”

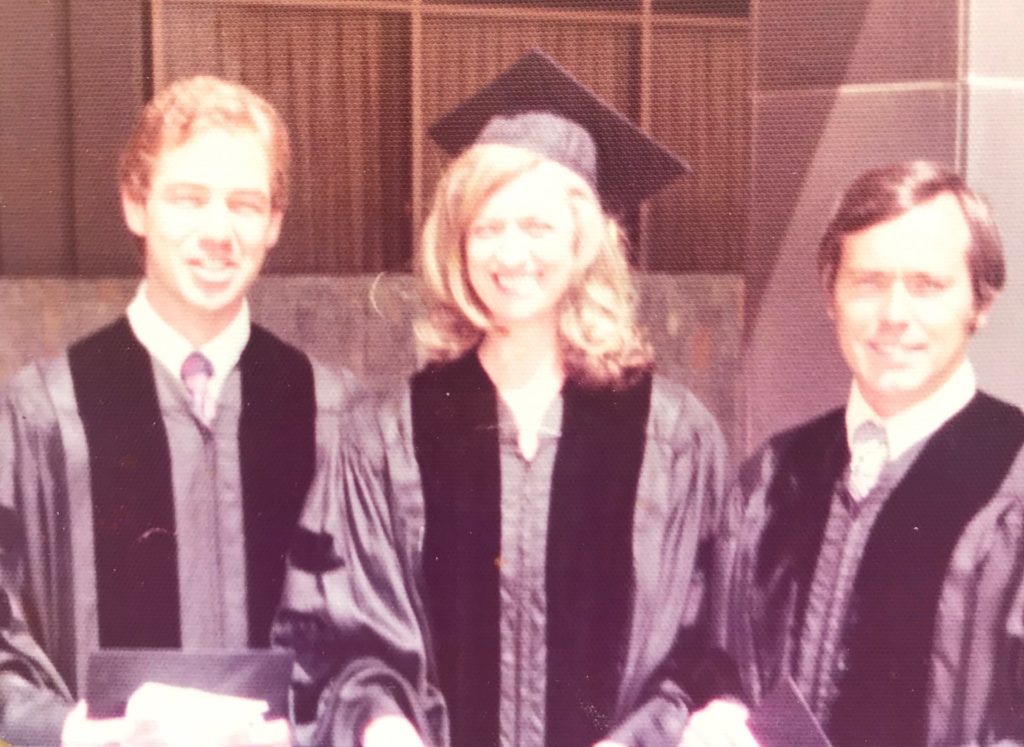

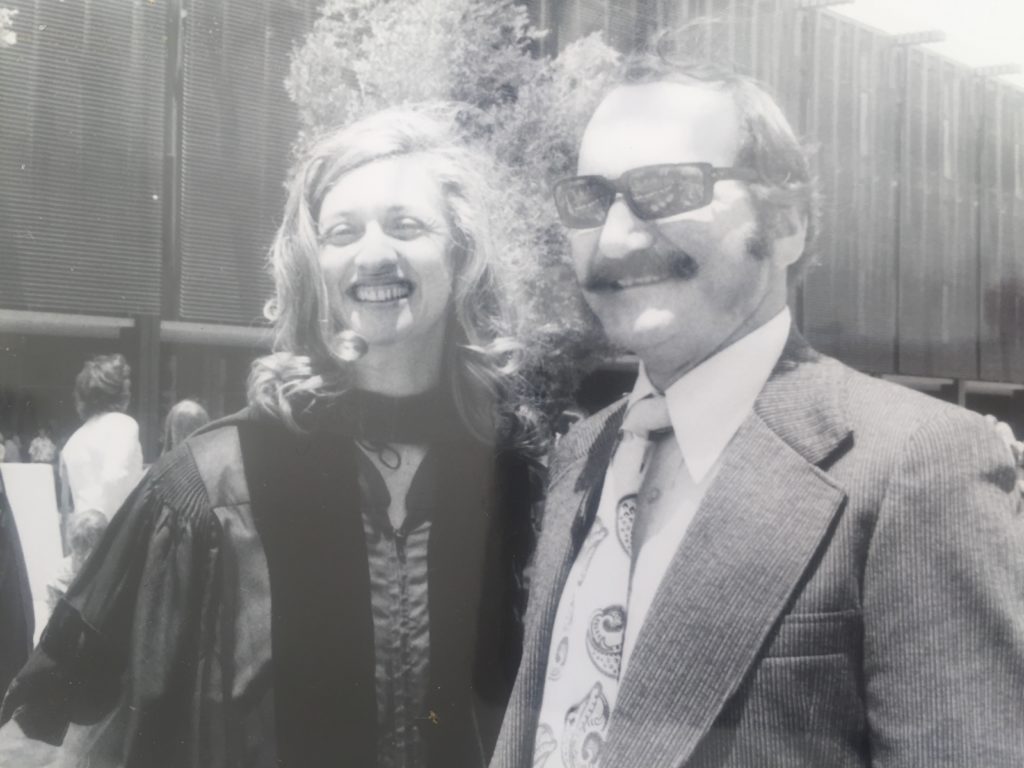

Doris with fellow Pepperdine Law School classmates on their graduation day in 1974 at the Plaza of the Flags in Santa Ana.

In fact, women made up only 4 percent of the legal profession in 1970 (11,000) and only 21 percent in 1991, according to Law Crossing’s A Short History of Women in Law, which elucidates how challenging it has been historically for women to enter the legal profession. Some highlights:

“Why was the law so resistant to women practitioners? Karen Berger Morello wrote in her 1987 history of women in the legal profession, The Invisible Bar (pp. x-xi): The reasons for the resistance to women in the law can never be fully explained, but it is likely that it has to do with the law’s close relationship to power in our society. . . . While entry into the medical profession might be justified as a natural extension of women’s nurturing role, the law was clearly an all-male domain, closest to the center of power that was not to be invaded or changed by females.”

“… Obtaining employment after law school was extraordinarily difficult, no matter how brilliant a woman’s record. Many law firms and judges would not even interview women. After graduating third in her Stanford class in 1952, Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor was offered a job as legal secretary by one of San Francisco’s leading firms. When D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg graduated first in her class from Columbia in 1959, she could not obtain a clerkship with the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York. The few firms that actually hired women in the fifties and sixties expected them to do trusts and estates work and stay in the library. Women did not go to court and had no client contact. Most women lawyers turned to government service, but only on the civil side. Federal and state prosecutors made it clear that they would have no women on their teams. The only area of criminal law open to women was legal services for the indigent, where the pay was (and is) very low. The few women in private practice had to content themselves with the one area of the law thought to be appropriate for them: family and juveniles – the ‘domestic sphere’ of the law.”

Doris did everything she could to help her Legal Aid clients, who were mostly poor Latino women. “I had this huge caseload — 600 cases!”

Doris was subsequently hired by Santa Ana’s City Attorney Office; and while working as city attorney got her master’s in tax law, again studying and going to school at night.

One of her biggest cases was the 1994 Orange County bankruptcy, which when it was declared was the first municipal bankruptcy in the country.

She retired in 1997.

“It was time,” she said. Doris was paid less than her male colleagues throughout her law career, but she took great pride in her work.

“My philosophy is that this is a democracy, and it’s such a beautiful democracy that we have — it’s why people from all over the world want to come here — because they don’t have that kind of freedom in other countries. I felt it was a gift to be able to understand how democracy works and how hard you really have to work to make sure that the process works for every freedom that you have. People that know me in the industry, they know how much I did for people.

“Also, the job sounded interesting and challenging, and when you do something that you feel proud of, you have a certain internal satisfaction that doesn’t go with pay. So that would be my advice to anybody, male or female who’s working — find a job you find interesting. And my husband was always the one who encouraged me.”

A Love for Art

After retiring, Doris began volunteering as a docent for the Orange County Museum of Art, founded in 1962 by 13 Newport Beach women who wanted a museum dedicated to modern art, she told me. I had never known that!

Doris has loved art since she was a little girl growing up in Squirrel Hill. “My sister is an artist and I always wanted to be connected to art,” Doris said.

She even traveled back to Pittsburgh in 1994 just to attend the opening of the Andy Warhol Museum. Carnegie Mellon built a beautiful seven-floor museum to honor his work, she told me. (Warhol, had, of course, studied there.) Having worked that summer when she was 16 in the Polish neighborhood that Warhol grew up in, she understood something of his childhood and blue-collar upbringing. “I absolutely had to see what art of his they had collected,” she said.

One of her favorite artists is Marc Chagall, the Belarusian artist who lived and worked most of his life in France. Doris and her son Fred snuck into the Palais Garnier (it happened to be closed when they were in Paris) determined to see the frescoes Chagall painted on the ceiling there.

She also loves the work of Gustav Klimt, who like her maternal grandparents was from Galicia. Doris told me stories behind some of Klimt’s work, including The Woman in Gold, his famous portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, which was stolen by the Nazis along with other paintings by Klimt belonging to the Altmann family in 1941. The paintings were kept by the Austrian government after the war, and only returned to Bloch-Bauer’s niece, Maria Altmann, some sixty years later with the help of a young Orange County attorney Randol Schoenberg. Schoenberg took Altmann’s case against the government of Austria and won. “It was remarkable as a new lawyer, how he did that,” Doris said.

Doris loves the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright — Wright’s Fallingwater house in Pennsylvania is an “architectural masterpiece,” she told me; as is the work of Austrian-American architect Richard Neutra, whose work you can see throughout Southern California. “Neutra’s Kaufman House in Palm Springs is another architectural masterpiece,” she said.

Doris and Dick were supporters of OCMA and (what we now know as part of) Segerstrom Center for the Arts since they first moved to Orange County, helping raise money for The Guilds.

Doris attended the 2018 reveal for the new OCMA building (that broke ground in September 2019) with architect Thom Mayne. She told Mayne she admired the way he designed the cascading front steps of the building and that it reminded her of the front steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Mayne told her that had been his inspiration. “It’s a gorgeous building,” she said.

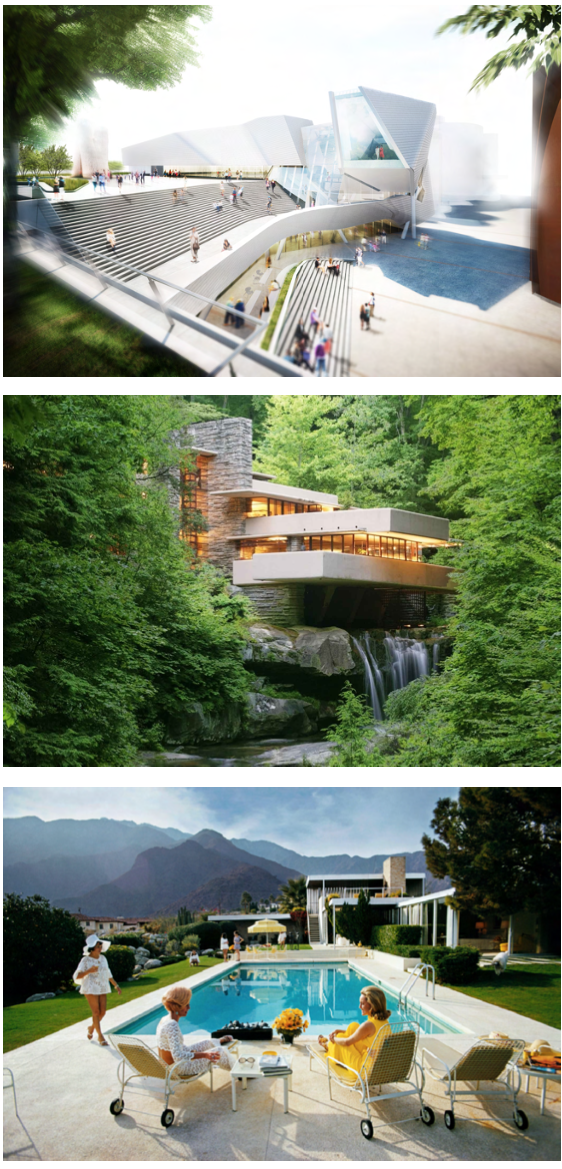

From top: One of Thom Mayne’s renderings of the new OCMA building, set to open in 2022; (Morphosis); Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, designed in 1939 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site; Slim Aaron’s iconic 1970s photograph of Richard Neutra’s 1946 Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs. Edgar Kaufmann, the businessman and philanthropist, and his wife, Liliane, commissioned both Wright & Neutra to design these residences: two of the most recognized landmarks of 20th-century American modernism architecture (Wikipedia).

Life Lessons

I also asked Doris some questions about lessons she learned over the course of her life and wisdom she might want to pass on to the next generation:

What are the most important lessons you feel you’ve learned over the course of your life?

Well, my husband used to say — and he always encouraged me in whatever job I had — don’t pay attention to anything that’s going on; just concentrate on doing your work and doing the best job you can. That is a lesson for life: to be proud of what you do. And that’s what I am; I’m proud of what I did. And I think what I did, somebody else might not have been able to do. I’m proud of my accomplishments. I’m proud of the way I did them. I have a great deal of satisfaction because of the way I performed my jobs.

And the other side of that is, you don’t want to do anything that you’ll be sorry for. See politicians, for example, they are compromising themselves for money all the time. I would not want to be a politician!”

The other one is, if you have an argument, always try to settle it amicably so that the other party will not go away feeling you took advantage of them. You never know when you might need that person again. Those are two things I learned.

If a young person came to you and asked you, “What’s the most important thing for living a good life?” — what would you say?

Well, I would say follow your interests. And use all of your talents to enrich your life with whatever job you take and whatever interests you have, because those are the things that will make you happiest.

In addition, I think every woman should learn skills to be able to support herself. That I learned from my mother. One of the most important things: women should be able to sustain themselves because we’re the ones that have the gift of life, which is the most precious gift that we have.

And just be good to yourself and be able to support yourself and take care of yourself.

Another thing I learned is there are always going to be people who will offer to help you. Yes, that’s true. That’s the American spirit. And that’s what I think living in this country does. If you need something, there will be people who will come. I have friends that would come and take me anywhere because they love me and I love them and they want to be helpful. And churches, too, are like that. Any church will help you; there will be people there that will help you. Yes. People believe in one another.

Doris in one of many dresses she designed & made herself. “Growing up poor, I could sew and make what I enjoyed. I designed my own wedding dress. And my mother also sewed.”

Kate – thanks for a lovely bio of my mom. I really love the way you brought her life to the page.

Thanks for your kind words, Fred. I’ve loved getting to know your mom!

I’m from the Pittsburgh area. It was delightful to read Kate McDonald’s account of the long and illustrious life of Doris Felman from Squirrel Hill, who attended high school and university at schools familiar to me. She loved and excelled at so many fields of endeavor, creating a rich and rewarding life by equally embracing challenges and opportunities. Her gratitude and enthusiasm are palpable.

Thank you, LL! I appreciate your kind words & will also pass on to Doris. She really is a powerful example for others!