Nurse Agnes Lyster during World War II.

It’s so easy to remember awkward, embarrassing situations with people — laugh and forget about them. It is much harder to search through all those ordinary moments shared and find what bound us.

Donald and I still laugh remembering when (we were living in Johannesburg in 1980), and my mother, Mary, and mother-in-law, Ag, missed their Comair plane for the game reserve and arrived back at our house in a taxi, just when we thought we could be alone with our new baby, Kate. We still are amused by Ag stopping to ask the gas station attendant how to work the air-conditioning in her BMW when taking my parents on a tour of the Cape Winelands. Her car didn’t have AC!

When I first was married and living in a foreign land, in South Africa, I had the great fortune to have this friend, my mother-in-law. Ag not only introduced me to many of her own friends, but let me be her doubles partner for tennis. She taught me delicious recipes, her banana bread amongst many, that we then offered for our après-tennis teas. She was a great cook and mentor for a newlywed never taught to cook. Her Sunday lunches still make me drool: homemade paté on her nutty brown bread, leg of lamb, roast potatoes, gem squash, grenadilla pudding. Ag’s tasty, uncomplicated meals I still make today. Ag, also, was an avid reader and introduced me to South African literature — Alan Paton, Laurens van der Post, J.M. Coetzee. She shared some of her favorite Irish, Scottish and British authors such as Edna O’Brien, J.I.M. Stewart and Laurie Lee.

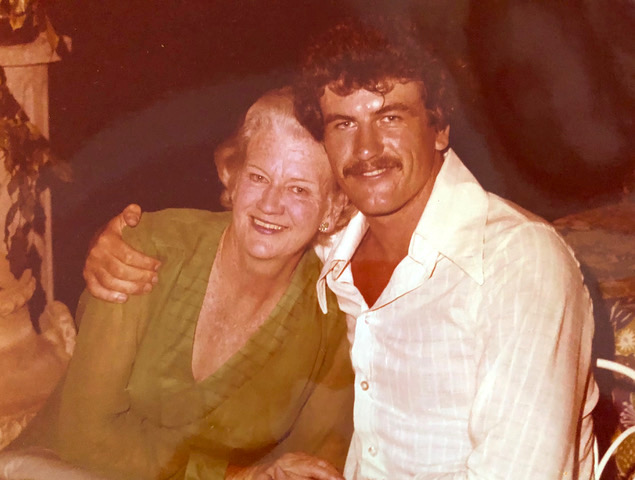

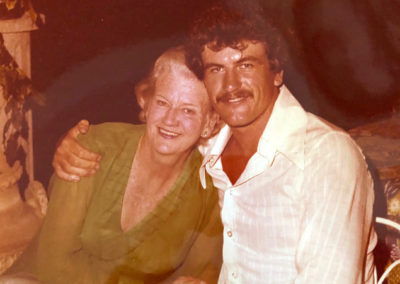

Ag and Donald at our wedding in Acapulco in 1978.

Ag took me on my first trip to Ireland in 1976 (special to me with my Irish ancestors) where I met some of her relatives in Kilkenny and thereabouts. Not many years ago, her Irish relatives welcomed me again, and Ag’s granddaughter, Kate, with a wonderful gathering. We stayed at an inn that had been a nursing home where some of the cousins had been born. Sadly, the spinster sisters, Liz and the invalid, Kay whom we had visited some 45 years ago had died. But Birdie attended and never failed to send Christmas cards. That day Ag and I spent at their farmhouse in the late 70s, we lunched on fresh trout served on bone china followed by great silver spoonfuls of raspberry crumble, smothered in thick Irish cream. Only after lunch did we meet Paddy, their only brother, who sat eating in the kitchen alone. The fisherman nodded to us from his tall Wellington boots.

Donald’s father & Agnes on their wedding day.

My mother-in-law grew up in colonial South Africa in a male world, a world for the most part dismissive of women to the home as wives and mothers. Ag had the fortune of good family values and support in her education at private schools where she starred as head girl: a caring leader and great athlete. (I still shiver to think of her daily morning swims right through the winter in an unheated pool.) She carried forward her interpersonal skills, sensitivity and capability into her nursing career. Although she wheeled one of her first patients into a glass door at Johannesburg General, she checked that he was fine and kept going. From that day, Ag vowed to only go through open doors. When her older sister, May, was beyond help from cancer and no longer herself, it was Ag who had the courage to stop the life support, despite religious dissent from the priest and the dismay of her twin sister, Doreen.

After the war, Agnes followed her heart into marriage and its attendant cultural expectation of wife and mother as her job, her life. She had three children under three (and much later, her lovely fourth) and a husband intent upon a fortune. Ag nourished her children with her kind heart, a heart that often took the bruising for them — those harsh demands and angry words from their father — softening them for their sensitive palates.

She was a trekker, showing them some of the many wonders of their natural African world, the flora and fauna of the Western Cape such as at du Toit’s Kloof where they would go camping. Did she object when her boys emptied their pillowcases of captured snakes into their drained swimming pool? Did Ag keep her cool when those tiny legs barely able to reach the gas pedal, stepped on it, squinting through the steering wheel, driving brother and sister down Main Road, Kenilworth while she was in the butcher’s? Who could count the times she drove them surfing or wherever they wanted to go?

She was a trekker, showing them some of the many wonders of their natural African world, the flora and fauna of the Western Cape such as at du Toit’s Kloof where they would go camping. Did she object when her boys emptied their pillowcases of captured snakes into their drained swimming pool? Did Ag keep her cool when those tiny legs barely able to reach the gas pedal, stepped on it, squinting through the steering wheel, driving brother and sister down Main Road, Kenilworth while she was in the butcher’s? Who could count the times she drove them surfing or wherever they wanted to go?

Why is a mother’s job the hardest in the world? Unschooled in it, she begins with the utter giving of self for the child: the blood of her body, the energy, agony and spirit of pushing this new life into the world and then the lifetime discipline of keeping her child’s welfare foremost: child first at all costs. This is her life sentence, one that is hard to parse when asked, What do you do? — that is if she was invited in the fifties to the Cape Town cocktail party anyway. Hard to parse when asked, what have you done, when her children have left home, and she has to start life anew when so ripe with age and so aware that ripeness is all.

Aerial view of Du Toit’s Kloof pass between Cape Town and Worcester in the Western Cape of South Africa.

The Black Sash was “founded in Johannesburg in 1955 as a non-violent resistance organisation for liberal white women.” (Wikipedia). Image: Public Domain.

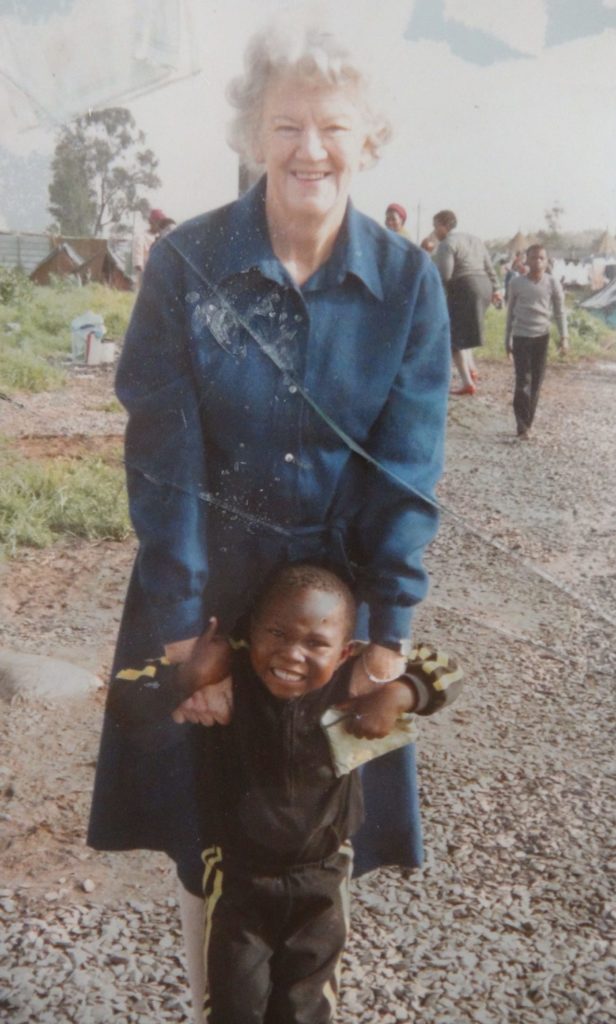

Although Ag’s primary job was being a good mother, she had a social conscience in a country and time when white women were to be seen, not heard. She was part of the Black Sash, the women’s organization that bravely demonstrated for equality in South Africa. She worked hard for Cape Town Child Welfare to protect and place endangered children. My husband remembers when he was hardly six, following his mother’s unflagging steps through the bush and wattle trees at Hout Bay in Cape Town to a dilapidated shack where a palsied child was hidden and later brought to care. Ag, also, was an advocate for Cape Mental Health Society, the first mental health society in South Africa (originally named, Society for the Care of the Feeble Minded) which was started in 1913. Ag helped raise funds for those with intellectual and psychological disabilities despite their race, by making a vocal appeal to the public. Even at her children’s sport’s days, she walked the bleachers with a cup to collect for Cape School Feeding. Agnes Lyster Macdonald was unrelenting for humanity. She was somebody.

It’s strange how one can love and be so loved by someone but know so little about her. There is so much about Ag I don’t know. I believe she kept a terrible sadness tight inside her. Whether it was from love lost from her husband, or perhaps a love lost before her marriage or maybe something, someone else, I’ll never know. Ag did build a wall of glass around herself where she retreated, tired, disappointed, but she didn’t disappear. She continued to knit sweaters for her grandbabies and fishing socks for her sons. Even though she was finally dismissed by her ex-husband, even though she much dismissed herself, Agnes Lyster Macdonald was someone singular, someone very loved.

Further Reading

• The history of the Black Sash in South Africa

• The Encyclopedia Brittanica on South African Literature

Photo Gallery

-

Nurse Agnes Lyster during World War II.

-

-

Flowers cover the fields along the Western Cape Coast after the winter rains.

-

Du Toit's Kloof pass between Cape Town and Worcester in the Western Cape.

-

The Kromrivier in Du Toit's Kloof Nature Reserve.

-

Young Macdonalds with their parents at Du Toit's Kloof in in the 50s.

-

Ag with her eldest son Dugald in Cape Town in the late 50s.

-

Ag and Donald at our wedding in Acapulco in 1978.

-

Kilkenny

-

Colorful Kilkenny

-

Kilkenny.

-

-

The Black Sash was “founded in Johannesburg in 1955 as a non-violent resistance organisation for liberal white women.” (Wikipedia).

-

-

Cassidy, I have wondered for years about you and Donald and your lives together. I came upon this tribute to your mother-in-law Agnes. I am still in touch with a few of our fellow students from Manchester College including Ellen Devaney Smith, Marie Donovan and Kit Cunningham. I married Doug Riley and we have three grow children! I would love to reconnect if you get this message and want to respond. Regards, Eileen Carr Riley